Open Tabs

Kinds of Love that Aren't Romantic Love

Louder for the people at the back please! 😆

Dispatch #49: Notes to Self

Some favorites:

- “The strongest dancers in my dance class take the combo and make it their own. Like all great artists, they combine foundational technique with a unique wildness. And they commit to it. A lesson for artists of any medium.”

- “For goodness’ sake, wait your turn to exit a plane.”

- “When you see a cute dog, make sure to say, ‘Hey look at that dog.’”

- “Try giving your anxiety a name and separate it from yourself. (“Thanks, for airing your concerns, Priscilla, but I’ll take it from here.”)”

(Found via Austin Kleon’s newsletter)

The Whippet #187: Hooves, stripes, paws and antler tips

Two super interesting ideas inside: the term “conditioning” as “a term that lets you bypass the issue of whether something is trauma or not” and coping mechanisms as “technical debt”.

(I like the second idea a lot, being a software developing myself and being deeply familiar with technical debt.)

Mary Oliver, "Sometimes"

Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

The Ten Rules of a Zen Programmer

An interesting application of Zen philosophy to programming, found via Every Programmer Should Know. (It might interest me particularly because of my interest both in Zen Buddhism and programming.)

To briefly sum it up:

- Focus

- Keep your mind clear

- Beginner’s mind

- No ego

- There is no career goal

- Shut up

- Mindfulness. Care. Awareness

- There is no boss

- Do something else

- There is nothing special

Erasers are wonderful

Part of a series in The Oatmeal titled “Eight Marvelous & Melancholy Things I’ve Learned About Creativity”. It’s an oldie (posted in 2020), but this bit resonated strongly with me:

Sometimes going down the wrong path isn’t a mistake – it’s a construction line.

The Decline of Deviance

Adam Mastroianni argues that culture, and society in general, has become more normalized and less “deviant”; not a completely bad thing, but it can have negative consequences. (Via Austin Kleon)

Some quick notes:

- Mastroianni argues that the main reason behind this shift is that the value of life has, literally, gone up: economic development and scientific advances have made life a lot less dangerous now, which in turn makes people more cautious and risk-averse

- This is mainly a good thing, but it also means the kind of risk-taking needed to make new discoveries and / or inventions becomes less common, and thus progress might stagnate.

- Therefore, we need new spaces / institutions that can encourage this kind of risk-taking, as a way to “keep the good kinds of weirdness alive”. We must choose to be weird.

Lucio, in Shakespeare's "Measure for Measure", via @shakespearemadeclear on Instagram

Our doubts are traitors, and make us lose the good we oft might win by fearing to attempt.

Divine comedy

Writer Julian Gough on why modern (western) literary fiction is heavily leaning towards the tragic, in opposition to the comic. (Via Austin Kleon)

A few interesting points:

- The Greeks believed comedy to be superior to tragedy: tragedy was the merely human view of life (we sicken, we die), while comedy tried to give us the relaxed, amusing perspective on our flawed selves afforded by the god’s view of life, from on high. (“We became as gods, laughing at our own follies.”)

- However: “The comic point of view—the gods’-eye view—is much more uncomfortable for a believer in one all-powerful God than it was for the polytheistic Greeks. To have the gods laughing at us through our fictions is acceptable if the gods are multiple, and flawed like us, laughing in recognition and sympathy: if they are Greek gods. But to have the single omnipotent, omniscient God who made us laughing at us is a very different thing: sadistic, and almost unbearable. We do not wish to hear the sound of one God laughing.”

- “The various eastern philosophies give us other high vantage points. Indeed, both physics and Zen can handle laughter, and are superb tools for writing the western comic novel because they do not require absolute faith and they do not claim absolute certainty.”

- One of the reasons modern western literary fiction overvalues tragedy is because our inheritance is lop-sided: a greater range of classical tragedies have survived, compared to the amount of classical comedies:

Plays that say, “Boy, it’s a tough job, leading a nation” tend to survive; plays that say, “Our leaders are dumb arseholes, just like us” tend not to.

- The novel could have been (or might be, in the future) a way out, because it was invented after Aristotle, and so had no classical canon and could go wild into comedy territory

The Em Dash Responds to the AI Allegations

Exactly what it says in the tin, in the always humorous and entertaining style of McSweeney’s :D

The Grammar of Fantasy and the Fantastic Binomial: Beloved Italian Children’s Book Author Gianni Rodari on Creativity and the Key to Great Storytelling

If a society based on the myth of productivity (and on the reality of profit) needs only half-formed human beings — loyal executors, diligent imitators, and docile instruments without a will of their own — that means there is something wrong with this society and it needs to be changed posthaste. To change it, creative human beings are needed, people who know how to make full use of the imagination.

(Vía Austin Kleon)

James Tate, "Dream On"

Some people go their whole lives

without ever writing a single poem.

(Vía Austin Kleon)

Langston Hughes, "Dreams"

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

(Vía Austin Kleon)

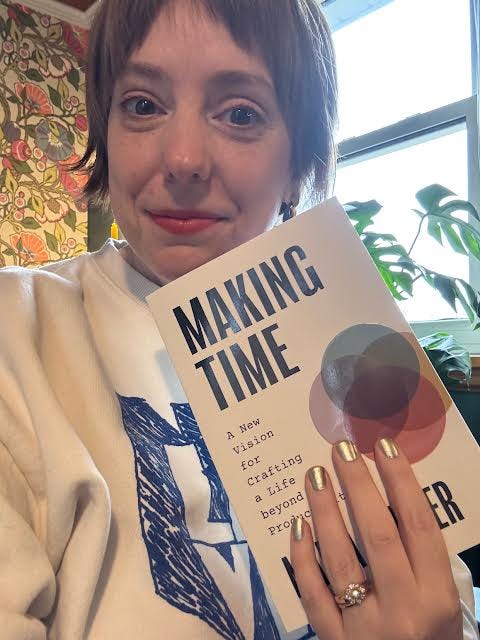

“I should’ve started earlier” - Make Human by Maria Bowler

Part of a month-long series of daily meditations “to serve as spiritual fuel for you, a culture maker”. However, I think these are applicable to life in general, even if we don’t consider ourselves “culture makers”.

One of the interesting bits:

Nothing will snuff out the imagination faster than sneering at yourself for what you haven’t done in the past. The way you treat the actions and performance of your past self not only inhibits the actions of your present self, but unless it’s changed, it will be the exact same way that your future self treats what you do today.

Epictetus (via "3-2-1: A simple practice for peace, how to become disciplined, and being bold")

Don’t explain your philosophy. Embody it.

3-2-1: A simple practice for peace, how to become disciplined, and being bold

Intelligence isn’t just about what you know. It is also the ability to avoid being your own bottleneck.

- If you lack the skills, be willing to look foolish while you learn them.

- If you lack the connections, be courageous enough to reach out and build them.

- If you feel uncertain, be bold enough to figure it out along the way.

Many people have the ability, but they talk themselves out of trying.

#56: "How to Write a Novel with the Kitchen Sink Thrown In" by Amber Sparks, author of HAPPY PEOPLE DON'T LIVE HERE

Some advice from author Amber Sparks on how to use all the interesting bits of information one comes across / collects. It is targeted at fiction authors, but maybe, as Austin Kleon puts it, it can be useful for non-fiction authors or, dare I say, everyone else.

To wit:

- Buy a LOT of notebooks and start separating your interesting things by topic

- Get a bulletin board or really big piece of paper or reserve a wall in your house or office or apartment and then use it to connect your ideas with red string like in the detective shows (or the meme of the crazy conspiracy guy 😆)

- Think about the characters you have, and how you can feed them the information you’re gathering

- Jump around in time: time travelers, storylines happening in different times, flashbacks, etc.

- Remember the iceberg: not everything needs to be in the book

- Pare back: if it doesn’t fit, then it doesn’t fit

Building personal apps with open source and AI

Again on the topic on personal apps, this time from the folks at GitHub and focusing also on how open-source code and generative AI can ease the process and be a multiplier (opposed to a replacement).

An app can be a home-cooked meal

Robin Sloan on the charm of making niche apps for very small groups of people, and how it is analogous to home cooking.

Fuzzy computing

Matt Holden on how generative AI can be though of as a tool for “fuzzy” computing, i.e. a tool with more permissible inputs, which in time makes personal computing more accessible (and/or accessible to more people)

How To Finish

Grant Snider on how to see creative projects to their completion, which might be as important as getting them started.

Related (possibly😅):

- Quantity leads to quality (the origin of a parable), on Austin Kleon’s blog, about how finishing more things can lead to a better quality on said things

- oblique strategies for starting a new project , on personal canon, which despite the title covers both starting and finishing as skills

- The Imperfectionist: Seventy per cent: “If you’re 70% sure a decision is the right one, implement it.”

Tips To Break Your Online Addiction: Garden

This is an oldie (2011), but as relevant as ever. Randy Murray advises taking gardening as a hobby to counterbalance the hours spent online, and the intervening years have only furthered his point of having offline hobbies as an antidote to the ills of the online world.

One thing after another - Austin Kleon

It is better to do your own duty / badly than to perfectly do / another’s….

How to turn down an invitation - Letters of Note

Dear Mr. Adams:

Thanks for your letter inviting me to join the Committee of the Arts and Sciences for Eisenhower.

I must decline, for secret reasons.

I’m using this from now on 😄

The Dark Side of a Second Brain

Taking notes so I can avoid these pitfalls ;)

Summing up:

- Digital hoarding - pure accumulation without revision

- Weakened memory - cognitive offloading results in weaker recall

- System maintenance trap - spending more time maintaining the system than using it

- Decision fatigue - hyper-organization and excessive complexity causes you to abandon the system

- False productivity - note-taking feels productive but doesn’t lead to learning

To avoid these pitfalls: keep your system simple, and give it a use, don’t just convert it into a dumping ground. If possible, link your notes. Simple systems can lead to serendipitous connections that a more complex organization will not allow.

15 years of blogging (and 3 reasons I keep going)

The title says it all, but I find the second reason in the list particularly interesting:

Every time I start a new post, I never know for sure where it’s going to go. This is what writing and making art is all about: not having something to say, but finding out what you have to say. It’s thinking on the page or the screen or in whatever materials you manipulate. Blogging has taught me to embrace this kind of not-knowing in my other art and my writing.

Typewriter interview with Sally Mann

My young friends are more than spies—they are my Virgilian guides through these purgatorial times. They offer me hope for the future; so smart and canny and kind—when I am with young people, I feel an uncharacteristic surge of optimism.

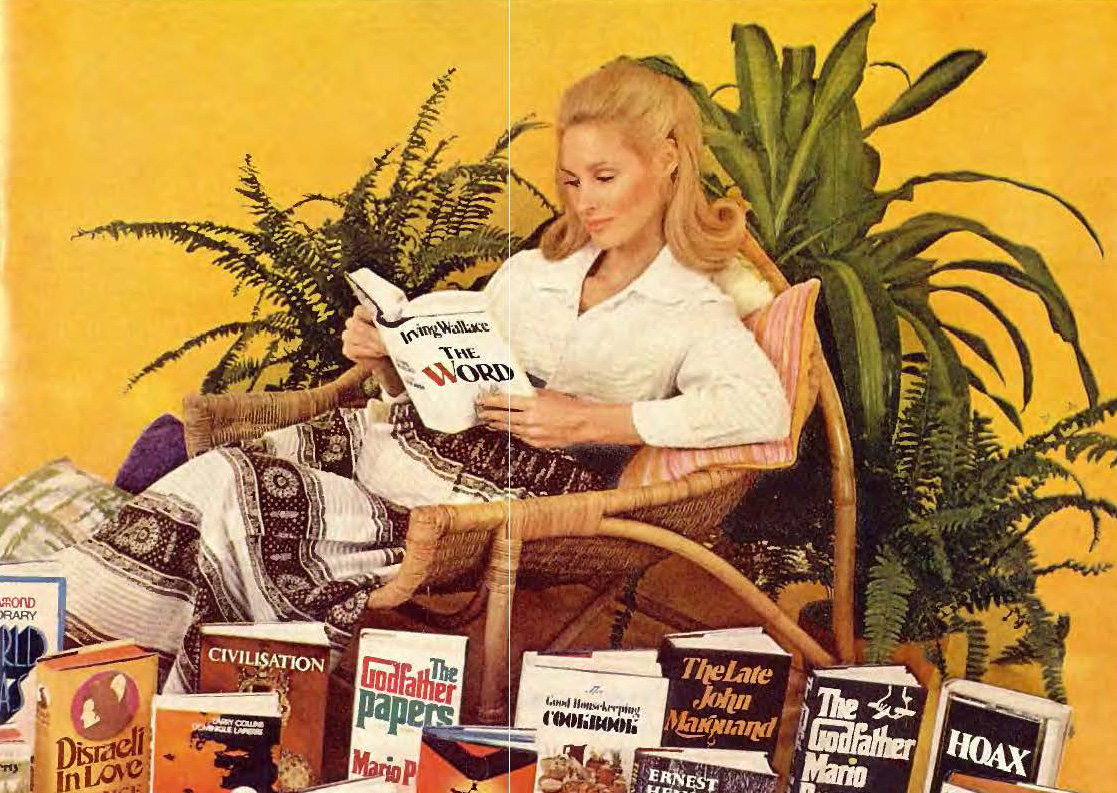

How To Read More

More advice on how to read more… which I maybe should start applying 😅.

Some points that stood out for me:

-

putting away your devices is step 1 😅

-

remember reading for pleasure:

Remember: pleasure fun hobby fun pleasure. Strip all that shit in your head away—your high school English teacher, the social media stuff about tracking how many books you read in a year, the folks who tell you it is political or resistance or moral or healthy like vegetables or a hack for getting ahead. It’s not competition. There is no test. It’s something you want to do. Full stop.

(Vía Austin Kleon)

the pleasures of reading – The Homebound Symphony

Useful advice for (re-)starting a reading habit. Via Austin Kleon.

Alive Internet Theory

Campbell Walker (a.k.a Struthless) offers a plan (and lots of inspiration) to make the theory in the title a reality (in opposition to the Dead Internet theory).

It’s really good seeing people out there fighting the good fight against the doom and gloom and the enshittification of the internet.

And yes, the phrase at the end is true: hope is punk.

Don't Follow Your Dreams, Follow Your Tools

Hank Green on what is, in his opinion, the secret to his success.

We have been sold the “follow your dreams ✨✨” advice a lot, and yet, as he puts it, if you blindly follow your dreams, you might miss on greater / more interesting opportunities. And this resonates a lot with me because I think I have been unknowingly following his advice: the last years have been a mix of having a set of loose goals and making use of the opportunities that landed on my lap, or whatever tools / options I had available at the moment.

64 Reasons To Celebrate Paul McCartney - by Ian Leslie

A very heartfelt homage to the last surviving Beatle, of interest to any Beatles fan. It is quite an oldie (from 2020), and in the intervening years the author has written a book, John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs.

(Found via Austin Kleon)

All the Ghosts You Will Be

Clicked on this video enticed by the title, and now I find myself with the very difficult task of summarizing it 😅.

Here’s my attempt: this is a video about how you might live forever, how humanity might live forever, and what drives humanity forward. Deeply philosophical, even existential.

The Substack AI Report - by Arielle Swedback - On Substack

Interesting insights from the publishing platform on the use of AI. If this is to be believed, then most of the creators that use AI leverage it as an aid / assistant for things such as brainstorming, research and writing assistance, instead of using it for plain generation.

Concerns are present even among the creators using AI, mostly on the ethical side as well as in the effects that AI use might have on their own creative voices / practice.

Contra el algoritmo: cultivar jardines digitales en vez de likes

Glad to see a video in Spanish on the topic of digital gardens… It even references the essay from Mike Caulfied, The Garden and the Stream: A Technopastoral, as well as the work of Maggie Appleton

Q&A: Conan’s Advice On Taking Risks Before You’re Ready | Conan O'Brien Needs A Friend

My lesson to everybody is: when your moment comes, you may not be ready, but you have to take it and then figure it out on the way.

PART 2: The INCREDIBLE Direction Billie Eilish and Finneas Gave Their Mixers - with Jon Castelli

If there’s anything I can say I hope I don’t lose in life, is the option to experience something for the first time, as if you were a child, and I feel like music is one of the ways that we can have that feeling

Also recommended if watching a couple guys nerding about music seems up your alley 😄

Hirayasumi: My Quarter-life Crisis Can't Be This Comfy

I’m a little older than the target audience mentioned in the video 😅, but I like the take on how to handle the challenges of transitioning to adulthood — which can be applied to life in general, I think:

Life is fast. Take it slow.

Françoise Sagan on the power of laziness - by Mason Currey

Not only do I like the take on laziness and work ethic by the French author of Bonjour Tristesse, this is also how I get most of my side projects done 😉:

The pleasure I derive from my work overcomes the laziness and I work for a while.

The First Known Story Ever Written | analysing the Epic of Gilgamesh

Came because I was curious about the story, stayed for the deep analysis of the origins of human civilization.

The highlights:

- The first civilization to ever put things into writing, writing about the invention of writing itself 🤯:

Until then, there had been no putting words in clay. Now, under that sun and on that day, it was indeed so. (Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta)

- at the 52:35 mark: “Though men are mortal, mankind itself is immortal”

- The distinction between the three states of being — animal, man, god — and how man is uniquely positioned because it has an awareness that the animal lacks, but also a fear of death that no god can understand and that leads it to live life to its fullest. This calls to mind how in Buddhism, there are also different realms of existence — one of them also corresponding to animals, other to humans, and other to devas (gods) — but only humans are uniquely positioned to escape the eternal cycle of death and rebirth [citation needed]

How Good Writers Work - by Michael Agger

Advice for writers, but might be useful for other jobs / endeavors / areas of life (emphasis in “might”).

On the Nature of Reality, Consciousness and (Artificial) Intelligence | Ashish Dahal

a reflection as old as time ;)

The highlights:

- I like how the author compares some of the ideas on the topic with concepts about machine learning (which I think is a topic very familiar to him). Not only is that a very good way of making unfamiliar concepts easier to understand, but it might also uncover connections previously unseen.

- “… the question ‘when will AI become conscious?’ is the wrong question. The right question is ‘what kinds of consciousness do current AI systems have, and how might those forms of consciousness evolve as the systems become more sophisticated?’”

- The idea of human consciousness as being augmented by (time-persistent) memory. I think the same idea applies to some other complex systems: without memory that persists across time, even a complex digital system is no better than a simple mechanical machine [reference needed]

3-2-1: On enthusiasm, playing to your strengths, and living one day at a time - James Clear

III.

“Education teaches you to analyze. Entrepreneurship teaches you to create.

The educated mindset is great at dissecting and criticizing. What did Shakespeare mean here? What were the major forces of this historical period? What is the limiting reagent in this chemical reaction?

The entrepreneurial mindset is great at building and improving. Design a better product. Craft a new marketing plan. Stop talking about what’s wrong and make something better.

The trick is to keep learning, but to never lose your ability to build.”

Some notes on failure

Hello Maker,

Your sweet words about (and pictures of) Making Timeare so darn beautiful. Thank you for sharing them with me; I wrote the book for you, so I’m so happy it can be in your hands now.

I have two events coming up that I’d love to see you at. They’re free, just RSVP!

**Minneapolis, MN: **Feb. 11 at 7pm. Open Book

**New York, NY: **Feb. 19 at 7pm. 91 Leonard St.

I promise to only send you things that nourish your attention.

Now, for some notes on failure

I think I discovered something about failure that I didn’t know before.

I’ll tell you about it, but first I’ll fail to tell you about it.

I hear agreement all over the political spectrum that our systems are failing.

We all act like we know what failure is, even as we’re looking at different problems.

In the thirteen years I have lived in the U.S., I have never heard anyone say they think the American educational system is successful.

But people have gotten mad at me online when I’ve suggested it could actually be better in concrete ways, and that’s quite something. Like I’m being viciously naive.

Hope invites this aggression. Let’s call it Hope Aggression.

Failure might just be something that happens, but the pain of failure might be the shame of having hoped for another thing to happen.

This shame is cruel to our tenderest, most open heart. It sees a desire — a connection to possibility — and tries to squish it with its big toe.

So failure is not its own feeling: failure’s suffering arrives when hope meets shaming.

Hope is Oliver Twist wanting more, and shame is the horrified master:

When we fail, we are often the one who hoped, and we internalize the cruel master — to self, to other, to the world.

“How stupid of me to have hoped.”

“How dare they let me hope.”

Someone asked me on a podcast how I got to be where I am. First, I wondered where I am. Then I answered, “Failing a lot!”

Many dreams made me run, run, run toward them until they led me face-first into yellow brick walls.

Like this dream: Working at a magazine in New York City (read that with the reverence of a girl from Winnipeg)!

The reality: Living with two ornery roommates in a tiny apartment in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, taking four separate trains to work twice each day, all for the pleasure of accruing debt to keep going.

Not all failure is a single rejection. Sometimes it’s an accumulation of small resistances — an erosion of ease, a steady, impersonal no that seems to be coming from Life itself.

When faced with a pile of resistance, I want to ask, “Why is life rejecting me? What is wrong with me? What is wrong with this whole thing?”

This all suggests that longing is lack, that wanting is a wound that needs to heal as soon as possible.

Every dead end dismantled some illusion I didn’t know I was still serving. This brought me closer to reality (read: life itself), which is what I wanted in the first place.

Life does not reject us, but the shaming of our hope might make us want to reject the life within us.

That, more than failure, is the real loss.

Do you think a friend would enjoy this?

Thanks for being willing to work with possibility, folks. I appreciate you deeply.

Love,

Maria

Do not stop now. Do not ask why.

Hello Maker,

I can’t stop thinking how tender, precious, and fragile this life is — all of which make awe possible. It makes me want to write something like a non-sectarian sermon (which I kind of did, see below).

You’re reading this? Cool. Let’s make sure you get the next one.

But first, I guess a lot of people feel tender about birthdays, and today is my book’s birthday: MAKING TIME can now be in your hot little hands. How strange! Let me get my mind around it.

Let’s quantify this thing.

A book in numbers:

- 2 years and 7 months in the official process.

- 6 rounds of editing.

- 604 cups of coffee.

- 2 trips to an Airbnb in Wisconsin to wander in the woods and stare at the wall and sometimes type.

- 713 walks taken in my neighborhood.

- 56 “what do I doooooo” conversations and just as many tears.

this could be you

My ego, my producer-self, wants to count to get control. I want to manage what happens to me, the world, strangers, the climate, my image, my friends, my kid (et al.) so badly!

Yet today all I can think in the face of all of this — the abundance of grace and pain, the sheer excess pouring out of everything, I want to fall to my knees and touch the earth. Who am I to withhold my presence, hoard my ideas, and protect my ego?

Here is that sermon-shaped thing:

A homily for why

“You could not be born at a better period than the present, when we have lost everything.”

― Simone Weil, **Gravity and Grace**

Do not stop now. Do not ask why.

Create to find your center.

Create to meet the world with your highest intelligence.

Create because it is an act of generosity.

Create because your process reveals how to be part of the larger, collective process.

Create because your process and the world’s are inseparable.

Create to offer the world a reflection of its living contradictions.

Create because consuming will dull you.

Create because consuming the status quo’s imagination will shape you in its image.

Create because a blank page or a lump of clay reminds you: beginnings are possible.

Create to find the fertile silence within.

Create because that silence will teach you how to bear it.

Create because your community deserves to see beauty made real, now and always.

Create because you are a bell no one else can ring.

Create because shaping something outside yourself clarifies what’s within.

Create because sharing your consciousness — however you do it —bridges isolation and connection.

Create because making is a conversation with existence itself.

Create because to make something is to tell the universe: “I am listening. I am answering.”

Share this with your people

3 Easy Ways to Help Making Time Find Its People

Here’s how you can help it ripple outward into the world:

- Ask your library to carry it. Libraries are so good. They will be happy to hear your request! They often have forms on their website for requests like this.

- Goodread It. If you’re on Goodreads, mark it as “want to read.” And when you’ve read it, a short review (just one insight or thought that stuck with you) can go further than you think.

- Pass it on. If something in the book moves you, share it with a friend or post about it. We all trust the books our people swear by, and your voice can make that connection happen.

- Leave a comment on Amazon. A single sentence about what resonated with you is a big deal.

Thanks for helping this little book find its way; it means more than you know.

Love,

Maria

All is not well! (But some things are)

“My best teachers were not the ones who had all the answers. They were the ones deeply excited by questions they couldn’t answer.”

— Brian Greene, physicist

Novelist Marilynne Robinson on how to handle good luck

“I can only make sense of my unaccountable good fortune by assuming that it means I am under special obligation to make good use of it.”

Source: **The Paris Review Interviews: Volume IV

3-2-1: On the joy of losing, how to set expectations with others, and notes to myself

- “Remain playful as your responsibilities increase. It’s easy to become serious when people and results depend on you, but nearly everyone’s performance improves when they proceed lightly through the world.”

- “Although losing is never fun, there is a certain satisfaction that can be found on the other side of losing — but only when you give your all. To lose with half effort offers no pleasure in the moment and no peace in the long run. But if your ambitions were full and your attempt was genuine, after the sting of losing wears off you’ll be left with something resembling contentment. The reward is not always in winning, but in striving.”

-

I found this in a pile of notes to myself, and share here simply as food for thought… “You want two things:

-

Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity. No wasted movement. No wasted effort.

- Compounding. Every project should have a long runway and feed the others.”

Things That Aren't Doing the Thing

Preparing to do the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Scheduling time to do the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Making a to-do list for the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Telling people you’re going to do the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Messaging friends who may or may not be doing the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Writing a banger tweet about how you’re going to do the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Hating on yourself for not doing the thing isn’t doing the thing. Hating on other people who have done the thing isn’t doing the thing. Hating on the obstacles in the way of doing the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Fantasizing about all of the adoration you’ll receive once you do the thing isn’t doing the thing.

Reading about how to do the thing isn’t doing the thing. Reading about how other people did the thing isn’t doing the thing. Reading this essay isn’t doing the thing.

The only thing that is doing the thing is doing the thing.

Digital hygiene

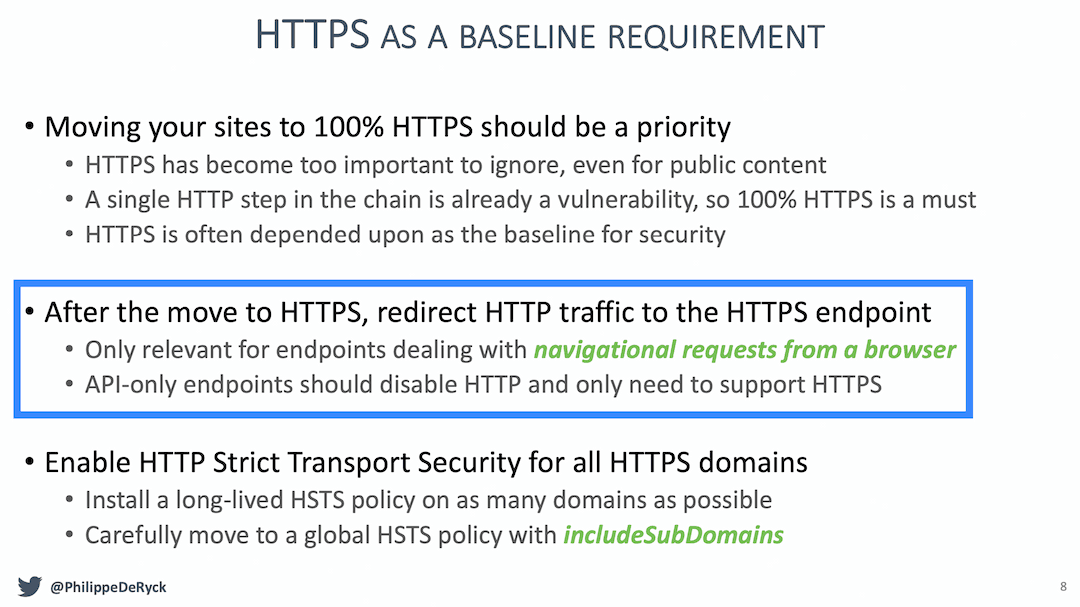

Every now and then I get reminded about the vast fraud apparatus of the internet, re-invigorating my pursuit of basic digital hygiene around privacy/security of day to day computing. The sketchiness starts with major tech companies who are incentivized to build comprehensive profiles of you, to monetize it directly for advertising, or sell it off to professional data broker companies who further enrich, de-anonymize, cross-reference and resell it further. Inevitable and regular data breaches eventually runoff and collect your information into dark web archives, feeding into a whole underground spammer / scammer industry of hacks, phishing, ransomware, credit card fraud, identity theft, etc. This guide is a collection of the most basic digital hygiene tips, starting with the most basic to a bit more niche.

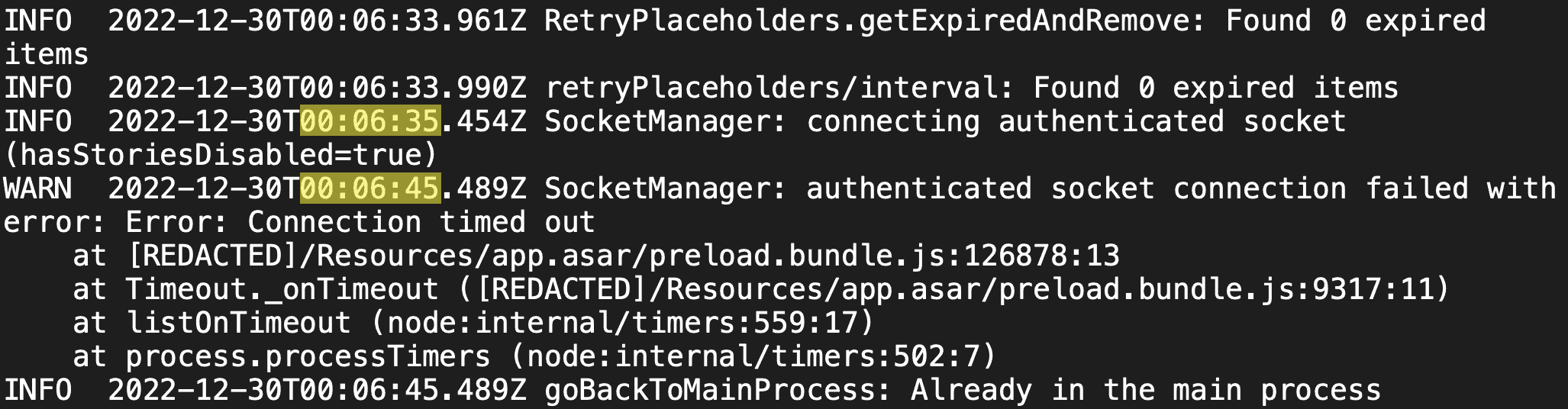

Screenshot 2025-03-18 at 10

Password manager. Your passwords are your “first factor”, i.e. “something you know”. Do not be a noob and mint new, unique, hard passwords for every website or service that you sign up with. Combine this with a browser extension to create and Autofill them super fast. For example, I use and like 1Password. This prevents your passwords from 1) being easy to guess or crack, and 2) leaking one single time, and opening doors to many other services. In return, we now have a central location for all your 1st factors (passwords), so we must make sure to secure it thoroughly, which brings us to…

Hardware security key. The most critical services in your life (e.g. Google, or 1Password) must be additionally secured with a “2nd factor”, i.e. “something you have”. An attacker would have to be in possession of both factors to gain access to these services. The most common 2nd factor implemented by many services is a phone number, the idea being that you get a text message with a pin code to enter in addition to your password. Clearly, this is much better than having no 2nd factor at all, but the use of a phone number is known to be extremely insecure due to the SIM swap attack. Basically, it turns out to be surprisingly easy for an attacker to call your phone company, pretend they are you, and get them to switch your phone number over to a new phone that they control. I know this sounds totally crazy but it is true, and I have many friends who are victims of this attack. Therefore, purchase and set up hardware security keys - the industrial strength protection standard. In particular, I like and use YubiKey. These devices generate and store a private key on the device secure element itself, so the private key is never materialized on a suspiciously general purpose computing device like your laptop. Once you set these up, an attacker will not only need to know your password, but have physical possession of your security key to log in to a service. Your risk of getting pwned has just decreased by about 1000X. Purchase and set up 2-3 keys and store them in different physical locations to prevent lockout should you physically lose one of the keys. The security keys support a few authentication methods. Look for “U2F” in the 2nd factor settings of your service as the strongest protection. E.g. Google and 1Password support it. Fallback on “TOTP” if you have to, and note that your YubiKeys can store TOTP private keys, so you can use the YubiKey Authenticator app to access them easily through NFC by touching your key to the phone to get your pin when logging in. This is significantly better than storing TOTP private keys on other (software) authenticator apps, because again you should not trust general purpose computing devices. It is beyond the scope of this post to go into full detail, but basically I strongly recommend the use of 2-3 YubiKeys to dramatically strengthen your digital security.

Biometrics. Biometrics are the third common authentication factor (“something you are”). E.g. if you’re on iOS I recommend setting up FaceID basically everywhere, e.g. to access the 1Password app and such.

Security questions. Dinosaur businesses are obsessed with the idea of security questions like “what is your mother’s maidan name?”, and force you to set them up from time to time. Clearly, these are in the category of “something you know” so they are basically passwords, but conveniently for scammers, they are easy to research out on the open internet and you should refuse any prompts to participate in this ridiculous “security” exercise. Instead, treat security questions like passwords, generate random answers to random questions, and store them in your 1Password along with your passwords.

Disk encryption. Always ensure that your computers use disk encryption. For example, on Macs this total no-brainer feature is called “File Vault”. This feature ensures that if your computer gets stolen, an attacker won’t be able to get the hard disk and go to town on all your data.

Internet of Things. More like @internetofshit. Whenever possible, avoid “smart” devices, which are essentially incredibly insecure, internet-connected computers that gather tons of data, get hacked all the time, and that people willingly place into their homes. These things have microphones, and they routinely send data back to the mothership for analytics and to “improve customer experience” lol ok. As an example, in my younger and naive years I once purchased a CO2 monitor from China that demanded to know everything about me and my precise physical location before it would tell me the amount of CO2 in my room. These devices are a huge and very common attack surface on your privacy and security and should be avoided.

Messaging. I recommend Signal instead of text messages because it end-to-end encrypts all your communications. In addition, it does not store metadata like many other apps do (e.g. iMessage, WhatsApp). Turn on disappearing messages (e.g. 90 days default is good). In my experience they are an information vulnerability with no significant upside.

Browser. I recommend Brave browser, which is a privacy-first browser based on Chromium. That means that basically all Chrome extensions work out of the box and the browser feels like Chrome, but without Google having front row seats to your entire digital life.

Search engine. I recommend Brave search, which you can set up as your default in the browser settings. Brave Search is a privacy-first search engine with its own index, unlike e.g. Duck Duck Go which is basically a nice skin for Bing, and is forced into weird partnerships with Microsoft that compromise user privacy. As with all services on this list, I pay $3/mo for Brave Premium because I prefer to be the customer, not the product in my digital life. I find that empirically, about 95% of my search engine queries are super simple website lookups, with the search engine basically acting as a tiny DNS. And if you’re not finding what you’re looking for, fallback to Google by just prepending “!g” to your search query, which will redirect it to Google.

Credit cards. Mint new, unique credit cards per merchant. There is no need to use one credit card on many services. This allows them to “link up” your purchasing across different services, and additionally it opens you up to credit card fraud because the services might leak your credit card number. I like and use privacy.com to mint new credit cards for every single transaction or merchant. You get a nice interface for all your spending and notifications for each swipe. You can also set limits on each credit card (e.g. $50/month etc.), which dramatically decreases the risk of being charged more than you expect. Additionally, with a privacy.com card you get to enter totally random information for your name and address when filling out billing information. This is huge, because there is simply no need and totally crazy that random internet merchants should be given your physical address. Which brings me to…

Address. There is no need to give out your physical address to the majority of random services and merchants on the internet. Use a virtual mail service. I currently use Earth Class Mail but tbh I’m a bit embarrassed by that and I’m looking to switch to Virtual Post Mail due to its much strong commitments to privacy, security, and its ownership structure and reputation. In any case, you get an address you can give out, they receive your mail, they scan it and digitize it, they have an app for you to quickly see it, and you can decide what to do with it (e.g. shred, forward, etc.). Not only do you gain security and privacy but also quite a bit of convenience.

Email. I still use gmail just due to sheer convenience, but I’ve started to partially use Proton Mail as well. And while we’re on email, a few more thoughts. Never click on any link inside any email you receive. Email addresses are extremely easy to spoof and you can never be guaranteed that the email you got is a phishing email from a scammer. Instead, I manually navigate to any service of interest and log in from there. In addition, disable image loading by default in your email’s settings. If you get an email that requires you to see images, you can click on “show images” to see them and it’s not a big deal at all. This is important because many services use embedded images to track you - they hide information inside the image URL you get, so when your email client loads the image, they can see that you opened the email. There’s just no need for that. Additionally, confusing images are one way scammers hide information to avoid being filtered by email servers as scam / spam.

VPN. If you wish to hide your IP/location to services, you can do so via VPN indirection. I recommend Mullvad VPN. I keep VPN off by default, but enable it selectively when I’m dealing with services I trust less and want more protection from.

DNS-based blocker. You can block ads by blocking entire domains at the DNS level. I like and use NextDNS, which blocks all kinds of ads and trackers. For more advanced users who like to tinker, pi-hole is the physical alternative.

Network monitor. I like and use The Little Snitch, which I have installed and running on my MacBook. This lets you see which apps are communicating, how much data and when, so you can keep track of what apps on your computer “call home” and how often. Any app that communicates too much is sus, and should potentially be uninstalled if you don’t expect the traffic.

Work-life separation. Ideally, do not log in or access any of your personal services on work computers. Most of them have company-operated spyware installed on them to protect the company’s intellectual property. This is all well and good and makes sense, but you should know that any activity on the computer is quite likely extensively logged (networking, keyloggers, screenshots, etc.) and possibly actively monitored by the security department.

I just want to live a secure digital life and establish harmonious relationships with products and services that leak only the necessary information. And I wish to pay for the software I use so that incentives are aligned and so that I am the customer. This is not trivial, but it is possible to approach with some determination and discipline.

Finally, what’s not on the list. I mostly still use Gmail + Gsuite because it’s just too convenient and pervasive. I also use 𝕏 instead of something exotic (e.g. Mastodon), trading off sovereignty for convenience. I don’t use a VoIP burner phone service (e.g. MySudo) but I am interested in it. I don’t really mint new/unique email addresses (e.g. SimpleLogin) but I want to. The journey continues. Let me know if there are other tips and tricks that should be on this list, e.g. you can DM me on 𝕏 at @karpathy.

taylor.town

Personal blog of Taylor Troesh, found via are.na, with all kinds of interesting musings. He writes about “learning, time, design, software, ideas, and humor”.

“How can I risk the truth even more?”

Maria Bowler in conversation with Emily Mohn-Slate about the intersection of mindfulness and creative practice.

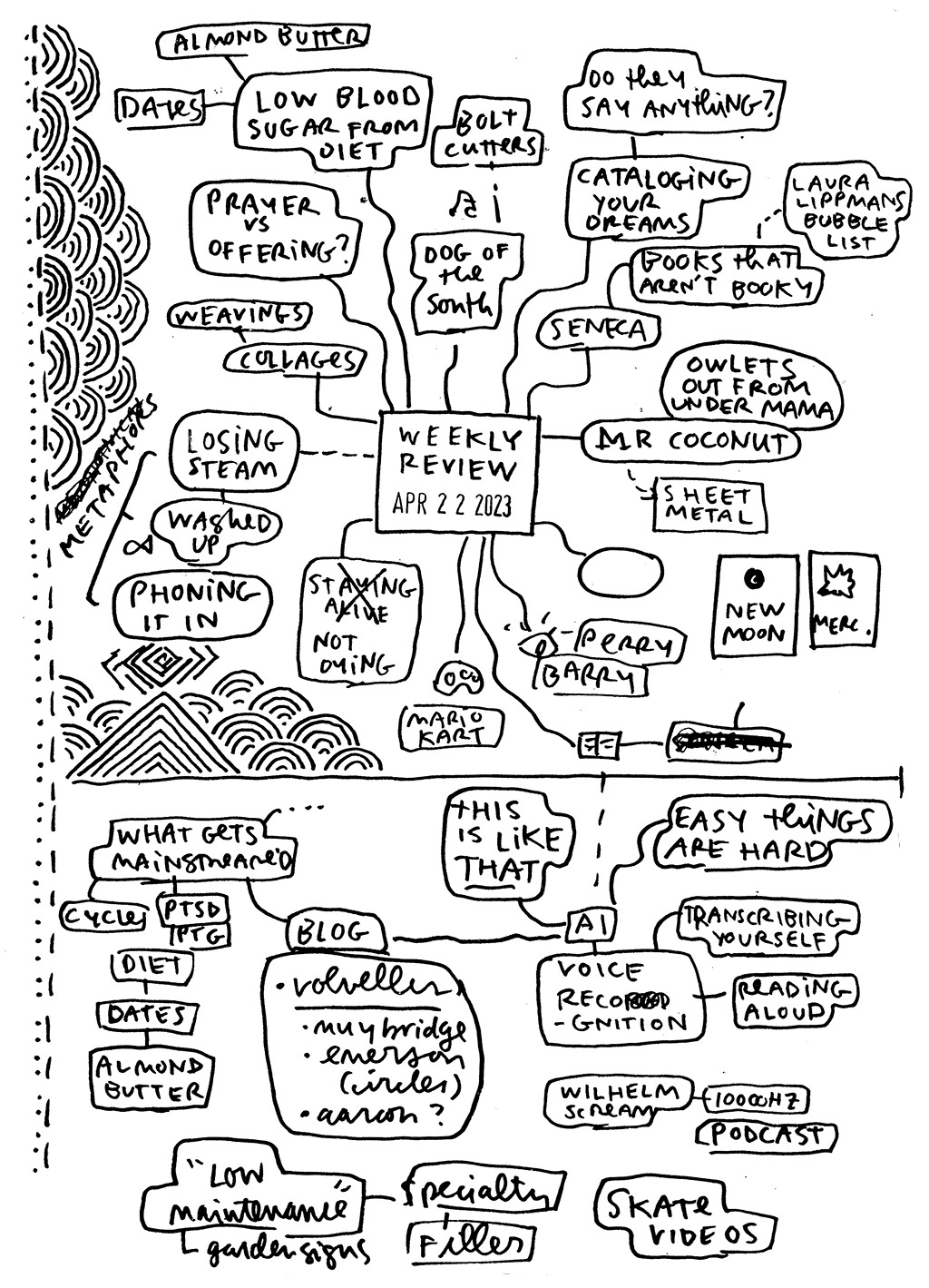

The weekly review - Austin Kleon

Hey y’all,

Today I wanted to talk about a tool that has been working for me lately: the weekly review.

I learned it from my friend Alan Jacobs, who, like me, is unfussy about “productivity” tools. His only real task-management tool is a calendar, and he uses that calendar to schedule regular times for reviewing his notes. He says:

No, the tools don’t really matter to me, and I have learned not to fuss about them. What’s essential is scheduling time — I set aside an hour each Monday morning and a whole morning on or near the first of every month — to go over all of those notes and do a kind of self-assessment. I sit down with my notebook and my computer and ask: Where am I in my current projects? What did I accomplish last week? What do I need to think about further? Is there any research or reading I need to be doing? What should be my priorities this week (or this month)? That kind of thing.

The minute I heard Alan explain this I knew it was exactly what I was missing in my creative life.

I’ve written about the importance of revisiting notebooks and how I’ve even created a blog widget to pull up old posts from my archives. And you could argue that my Friday newsletter is already a kind of weekly review. But that’s a public review — I’m going back through my week, and picking things that interested me that I think would interest y’all. What I also need is a private weekly review, a little bit of time for reflection. A system for getting my bearings. Figuring out where I’ve been and where I want to go next.

Speaking of not knowing where I’ve been and the need for review: I’m just now remembering that David Allen writes about the need for a weekly review in his classic, Getting Things Done.

Most people feel best about their work the week before their vacation, but it’s not because of the vacation itself. What do you do the last week before you leave on a big trip? You clean up, close up, clarify, and renegotiate all your agreements with yourself and others. I suggest that you do this weekly instead of yearly.

Allen suggests blocking out two hours early every Friday afternoon, to “clear your psychic decks so you can go into the weekend ready for refreshment and recreation, with nothing on your mind.“

Alan does Monday morning. Allen says Friday afternoon. Because I’m a weirdo, I’ve actually been doing my weekly review on Saturday morning, right after I get done writing in my diary.

Here’s what it looks like (yes, I know it’s weird to talk about needing a private review and then sharing it):

I do not expect this image to make any kind of sense to anyone other than me! But let me try to explain. Basically, what’s going on here is that I’m making two maps of my mind, divided by a line 2/3 down the page.

The map on top is for the things I was into or the things that happened during the week. I fill this out by re-reading my diary and my logbook and my blog and my newsletters.

The map on the bottom is for things I want to research or write about during the upcoming week. I often copy things from last week’s weekly review that I didn’t get to into this space.

(I make maps instead of lists because it activates the visual part of my brain — there’s something about seeing everything laid out in space that helps me see connections between everything. I would guess that for other people written lists might work better.)

And that’s it, really. Takes maybe a half hour to 45 minutes, but it’s really paid off over the last month or so and helped me keep better track of what I’m up to.

I’m going to stop there because I’d like to hear from y’all. Do you do a weekly review? What works best for you? Tell us in the comments:

(If anyone wants to share images, I’ll also start a thread in the chat.)

xoxo,

Austin

Story of a Poem: A Memoir: Amazon.co.uk: Zapruder, Matthew: 9781951213688: Books

From Austin Kleon’s newsletter, who has this to say about the book:

“Zapruder shares the ongoing drafts of a poem he’s working on — very #showyourwork — while also meditating on his experiences with writing poetry and being the father of an autistic son. Could a book be more up my alley? The way he unpacks his feelings about giftedness, overachieving, language, disability, and difference really spoke to me.”

Not everything will be okay (but some things will) - Austin Kleon

An image by Ryan Thacker at the end of Maira Kalman’s Creative Mornings talk

“There is a vast difference between positive thinking and existential courage.”

—Barbara Ehrenreich, **Bright-Sided

You know you’re in a bad spot when passing sidewalk chalk platitudes on your daily walk makes you murderous.

For me, yesterday, the breaking point was a hand-painted sign that read “EVERYTHING WILL BE OKAY.”

What fucking planet are these people living on?

My favorite cinematic misanthropes started conversing with each other.

“Where do they teach you how to talk like this?” Melvin Udall asked.

“What absolute twaddle,” Withnail agreed.

I was reminded of the story of G.K. Chesterton’s book, Platitudes Undone**:

In 1911, author Holbrook Jackson published a small book of aphorisms under the (mildly pretentious) title Platitudes in the Making: Precepts and Advices for Gentlefolk and gave a copy to his friend G.K. Chesterton. Chesterton, it seems, sat down with the book – and a green pencil – and wrote a response to each saying in the book. Presumably he then set the book down, and somehow, someway, it turned up in a San Francisco book shop in 1955, where it was purchased by a certain Dr. Alfred Kessler, an admirer of Chesterton. Every book collector dreams of such a find. Rather than keep the book to himself, however, Dr. Kessler and Ignatius Press have produced a facsimile edition. Remove the dust jacket, and you have a reproduction, in every particular, of that 1911 volume, together with all of Chesterton’s remarks. It’s a remarkable project, and a real treat for readers of Chesterton.

People are dying. Our leaders are corrupt. Things are not good.

But there’s still sunshine and birds and Gene Kelly dancing.

If we are going to paint the neighborhood with slogans, let’s at least honor each other’s grief and intelligence.

everything will be okay.

NOT everything will be okay BUT SOME THINGS WILL.

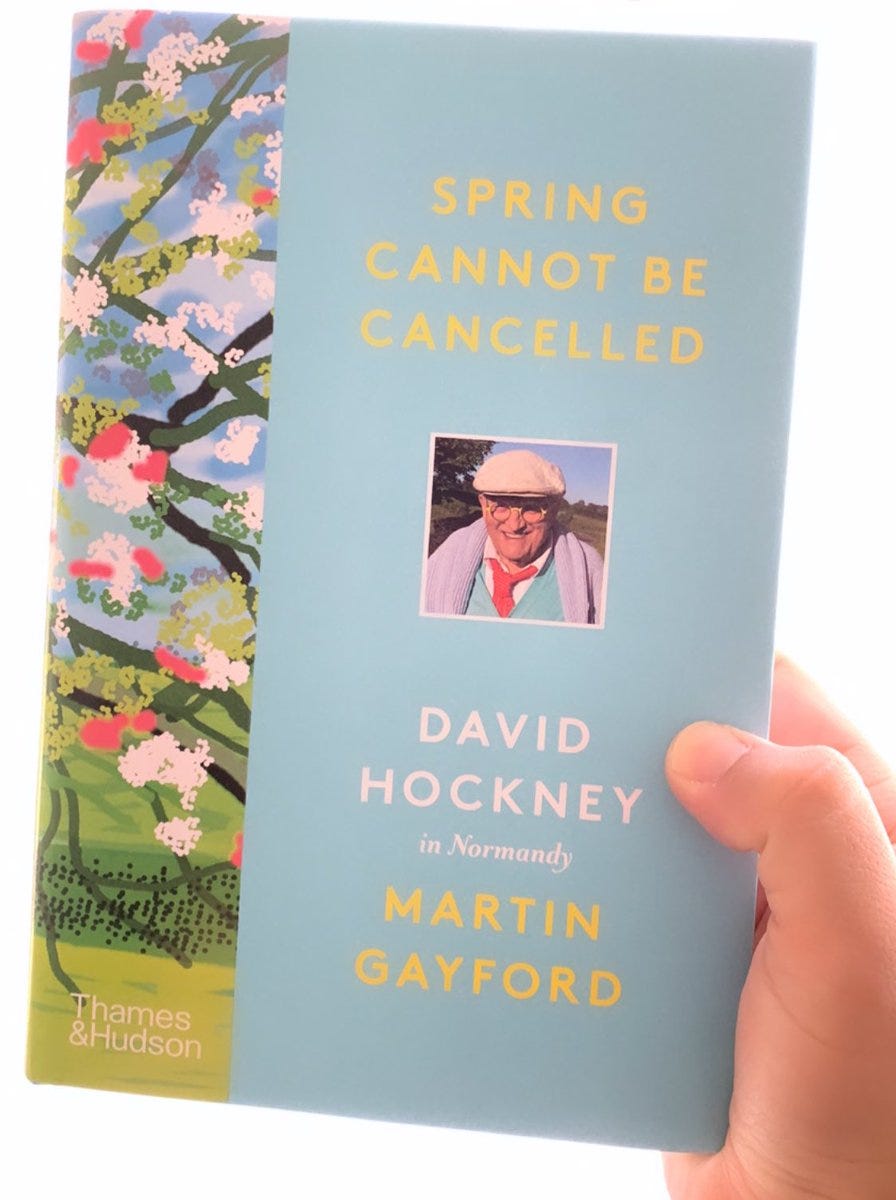

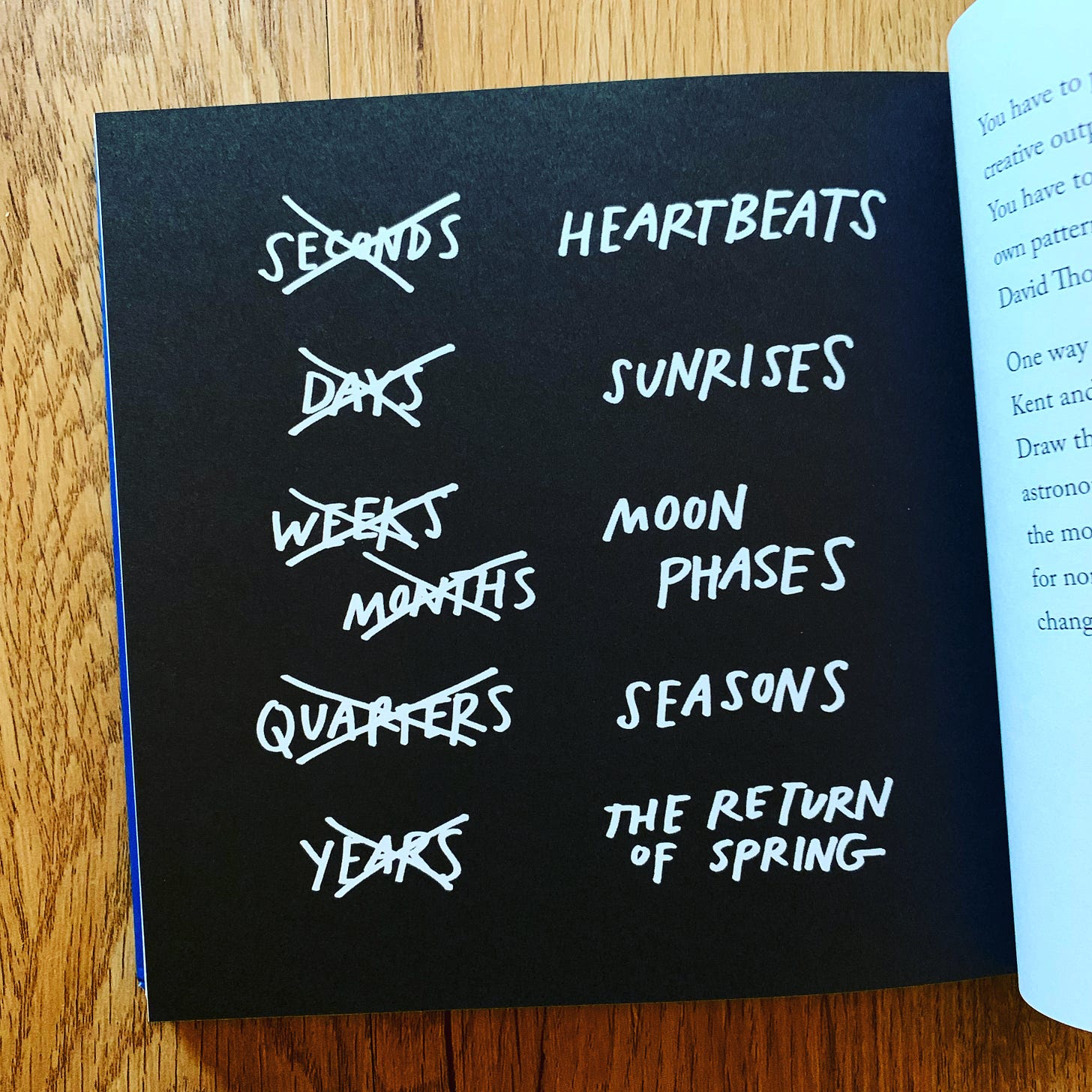

A spring bouquet

Hey y’all,

I’m in a gathering mood. Montaigne said he made bouquets of out of other writer’s flowers. I feel like making a spring bouquet.

Yesterday was the spring equinox in the northern hemisphere. The earth’s tilt is perpendicular to the sun’s rays, and it will now slowly tilt towards the light. We’re headed for summer now, while our neighbors in the southern hemisphere are headed towards winter.

I used to be “Mr. Autumn Man,” but spring and the new growth has meant more to me in recent years because of our new normal of nasty winter storms here in Austin, Texas.

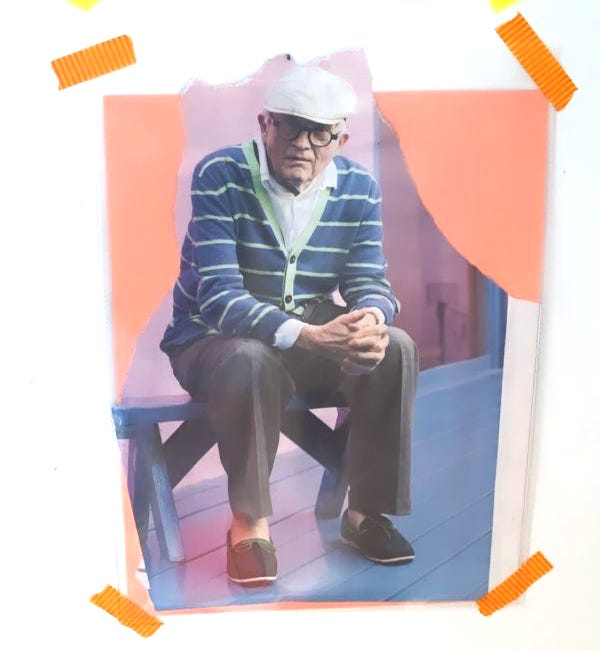

I started spring off last year by reading Martin Gayford’s Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy. It was the right book at just the right time. If you’re looking for a lift, I can’t recommend it enough.

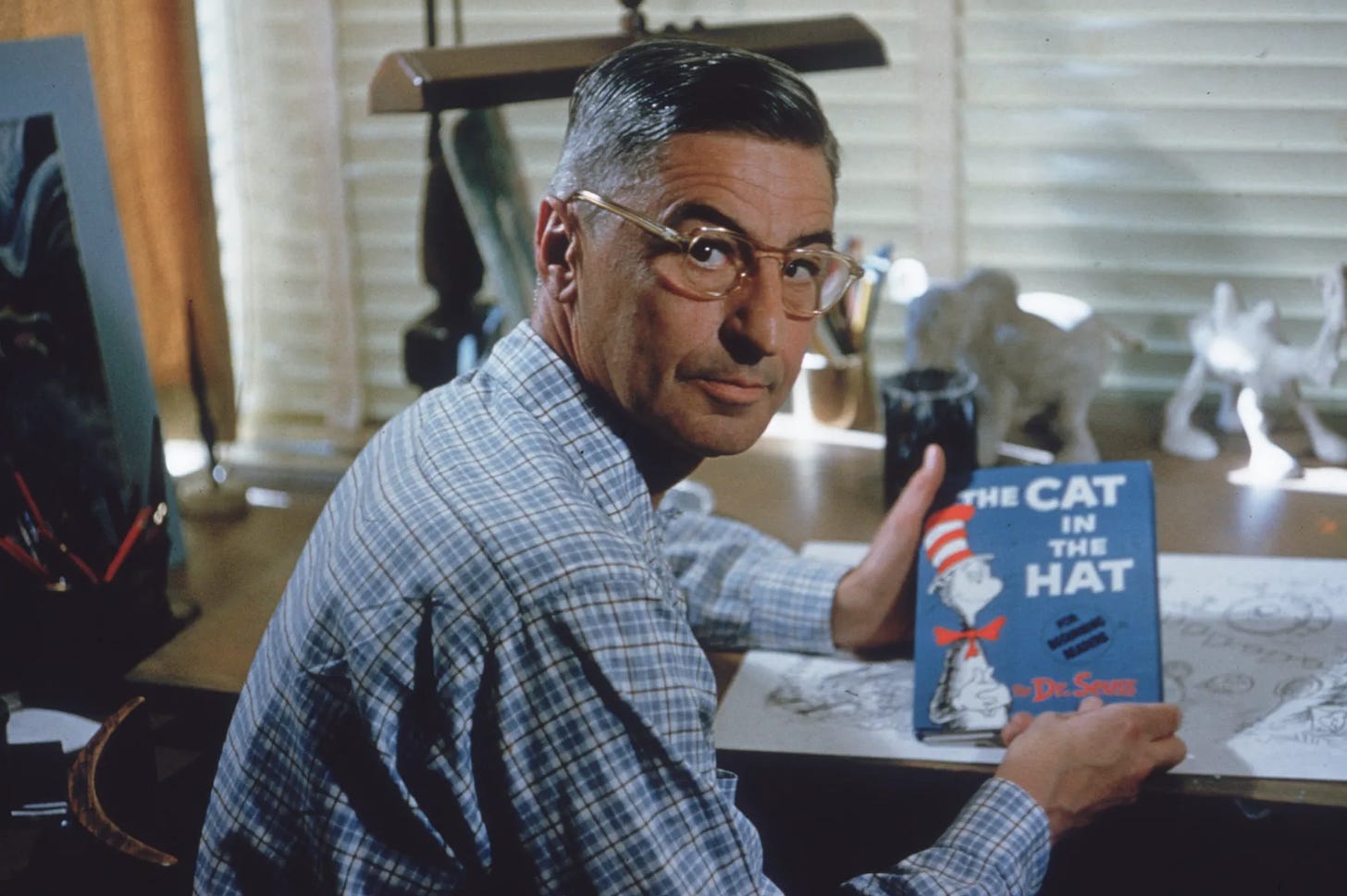

Hockney is one of my favorite artists. In Keep GoingI wrote that I want to make his words my own motto: “I’ll go on until I fall over.” (I also wrote about him and his relationship to technology around this time last year.)

In the studio I have a poster from his “The Arrival of Spring” show and near my desk I have a picture of him that stares at me, as if he’s saying, “Well? What are you waiting on? GET TO WORK.”

During the lockdown Hockney wrote:

I intend to carry on with my work, which I now see as very important. We have lost touch with nature rather foolishly as we are a part of it, not outside it. This will in time be over and then what? What have we learned? I am 83 years old, I will die. The cause of death is birth. The only real things in life are food and love in that order, just like our little dog Ruby. I really believe this and the source of art is love. I love life.

(A spring earworm has suddenly stuck in my head: Buck Owens singing “Love’s Gonna Live Here.”)

A page from Keep Going

In Joy Williams’ essay “Autumn” she writes about being careful about the optimism of spring:

There is no such thing as time going straight on to new things. This is an illusion. Okay? And clinging to this illusion makes it difficult to understand oneself and one’s life and what is happening to one. Time is repetition, a circle. This is obvious. Day and night, the seasons, tell us this. Even so, we don’t believe it. Time is not a circle, we think. Spring screams the opposite to us, of course, and summer seduces us into believing that we’re all going to live forever….

Horace was not seduced! Here he is in The Odes (IV, 7):

Gone is the whiteness

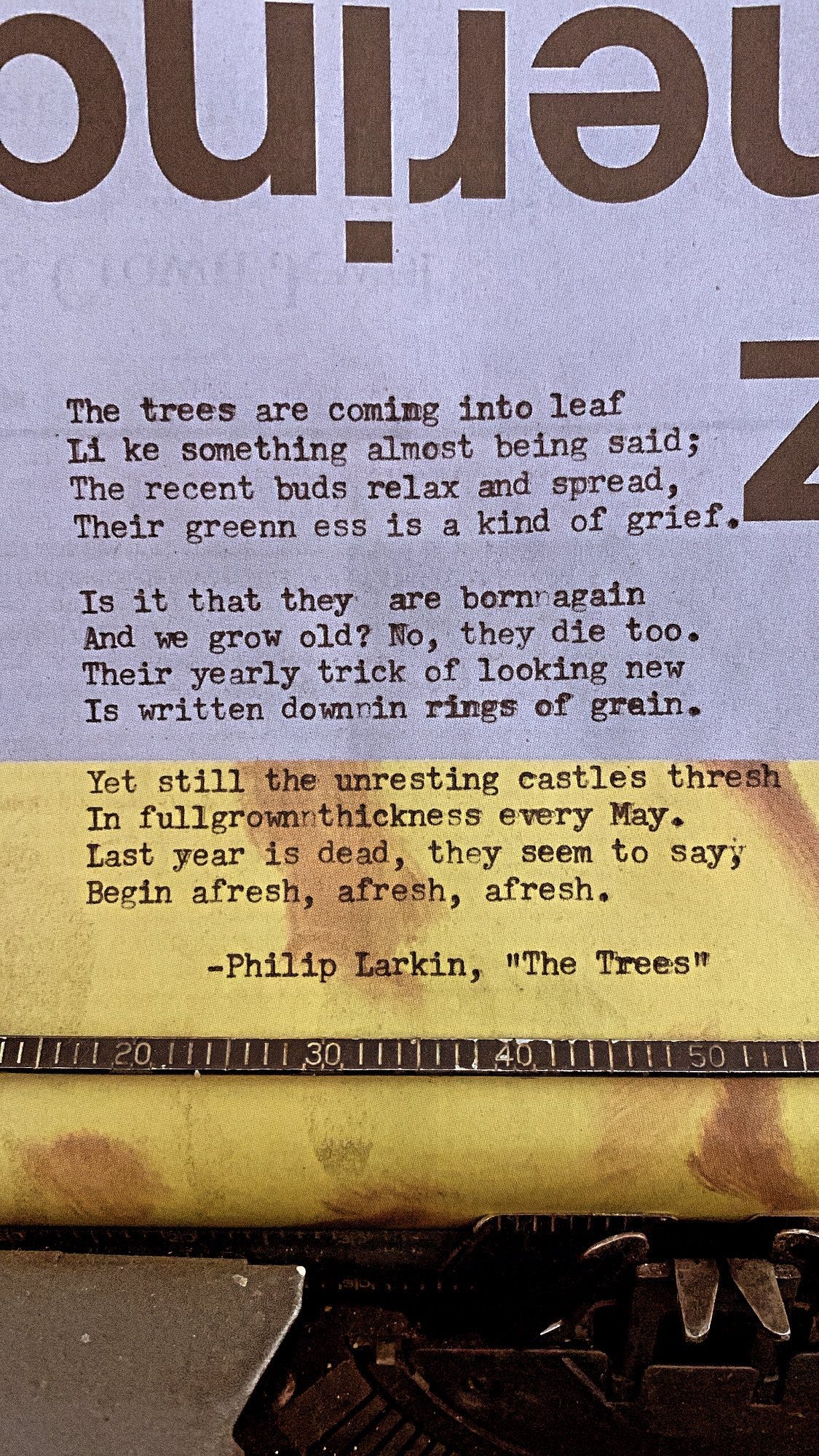

And neither was Philip Larkin — this is the time of year I recite his poem “The Trees” to myself: “The trees are coming into leaf / like something almost being said” but “their greenness is a kind of grief…”

While we’re on the subject of dark mixing with the light — gardening has provided me with yet another creative metaphor. I came across this fact while cutting up a book for the collage at the top of the page:

“Botanists used to think that the length of daylight a plant was exposed to determines whether it would form flowers. But… it’s the length of darkness that a plant experiences that plays the most crucial role.”

A taxonomy of plants:

(1) long-day (or, more accurately, short-night) plants that normally bloom in spring and summer

Like my friend Clayton Cubitt says, “The photographic rules of exposure also apply to life: you either need more light, or more time. And all the time in the world won’t help you if you don’t have any light.”

A snippet of my zine, The Creative Seasons

“I suppose an artist or any person who continues to grow is like a tree or any living thing,” writes Martin Gayford. “A plant takes in water, minerals, light, and carbon dioxide and transforms them into leaves and flowers. In the same way, people who continue to blossom also need to carry on processing fresh thoughts and experiences.”

But you must know what season you’re in! For me, this has been the year that somehow refuses to get started. But maybe the spring will also be a creative spring. It’s feeling just like it might be….

xoxo,

Austin

More Than Words: How to Think about Writing in the Age of AI : Warner, John: Amazon.co.uk: Books

Product description

Review

“Warner offers smart commentary on the downsides of AI, particularly its ability to bypass critical thinking, and the suggestions on adjusting to the software’s increasing popularity are thought-provoking… This provides plenty of food for thought.”–Publisher’s Weekly

“In lively prose and with many engaging personal anecdotes, [Warner] deftly explains how ChatGPT mines data for examples to imitate… anyone who loves to read and write, who teaches excellence and personal achievement, and who remains convinced that people are unique will find this book a welcome arrow in their humanist quiver.”–Kirkus Reviews

“A necessary intervention in all the marketing hype and overpromising about artificial intelligence. This book is a must-read for anyone who feels pressured to adopt this new technology: teachers, students, professional writers, and nonprofessional writers (emailers, all of us) alike. Warner challenges the notion we aren’t ‘innovating’ or ‘optimizing’ or churning out ‘content’ fast enough. He explores why writing, particularly in school, has become such an awful chore–for students to produce and teachers to grade. The fix here isn’t new software that promises to make brainstorming and drafting a breeze. Rather, we must revitalize the practices of care and curiosity together, and, in doing so, help foster our understanding of one another–an exercise in civics, not just in essay composition. More Than Words is honest about the struggles we all have with crafting written language, but it helps us see the real dangers that will come with its automation.”–Audrey Watters, author of Teaching Machines

“Does AI threaten the art of writing itself? As Warner’s wise, warm, and much-needed intervention shows us, the answer is no. By automating the production of low-quality text, AI companies can, however, threaten the practice and economics of writing. This lucid and compelling book gives us the tools to reject and resist what’s noxious about generative AI and to meaningfully engage with what it means to write, as a human, in a world increasingly overrun by cheap and meaningless content.”–Brian Merchant, author of Blood in the Machine

“Oh, how I’ve been waiting for this book! With his many years of experience as a writing teacher, Warner is the perfect guide for helping us understand what AI means for writers. Now is the perfect opportunity to rethink our ideas about writing and what’s so special about being a human who works with words. I stole a ton of inspiration from this book and so will you.”–Austin Kleon, author of New York Times bestseller Steal Like an Artist

“Reading this new contribution from Warner makes us realize what we’ve been missing in other works about, or generated by, AI: experienced, authentic writing by someone in charge of their craft, fully respecting the human on the other end. This work is deeply readable. Not that it is simplistic, but instead, that it’s so well written and deeply substantive that we find it moving and applicable. Sign me up for this level of cogency.”–Rick Wormeli, author of Fair Isn’t Always Equal

“This book is essential reading for everyone–writers, students, teachers, parents, administrators–navigating the evolving landscape of AI writing tools and tech company hype. Warner makes a powerful case for the role of writing as thinking, writing as feeling, and writing as a human practice that will endure in the AI era. Warner’s clear-eyed wisdom about writing and teaching, and his engaging–and very human–voice, will leave readers inspired, informed, and optimistic about the future of writing.”–Jane Rosenzweig, director, Harvard College Writing Center

“This is the book with everything you need to know about writing and AI all in one place, lucidly and passionately argued. Every teacher and every professor should have this book. Every legislator, every policymaker. Every parent and every student. Every publisher of newspapers, websites, and books. Here, John Warner exposes the ethical wasteland of replacing human writing with machine-made ‘content.’ He warns of the profound environmental costs of AI–trillions of gallons of water to cool data servers that produce nonsense no one wants or needs. And he reminds us only humans can write and only humans can read, and that writing is thinking–and if we allow machines to write for ourselves, then we’ve allowed them to think for us, too. And that is the sorriest thing a human could do. But Warner provides a better path. This is a scary book, but a hopeful one, too, and an absolutely essential one.”–Dave Eggers

“All educators should read this thoughtful analysis of the impact of generative artificial intelligence on themselves, their students, and education more generally. Warner’s arguments rest on the notion that authentic writing tasks are fully intertwined with thinking, feeling, and learning. But from those foundations, he discovers deeper insights about how humans and machines interact, and why we should never allow automation to supplant the work that makes us human.”–James M. Lang, author of Distracted

About the Author

John Warner is a writer, speaker, researcher, and consultant. The former editor of McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, he is the author of the books Why They Can’t Write and The Writer’s Practice. As “the Biblioracle,” Warner is a weekly columnist at the Chicago Tribune and writes the newsletter The Biblioracle Recommends. He is affiliate faculty at the College of Charleston and lives in Folly Beach, South Carolina.

Art advice with Beth Pickens

Hey y’all,

Last week I had the pleasure to chat with art coach Beth Pickens, author of Make Your Art No Matter What and *Your Art Will Save Your Life**. *Beth and I share many of the same core messages, but I come at making art from the inside of being a working artist and Beth comes at it from the outside of working with artists, so she picks up things that I miss.

You can watch our conversation in the video above or listen to it below:

1×

0:00

- 1:21:04

Audio playback is not supported on your browser. Please upgrade.

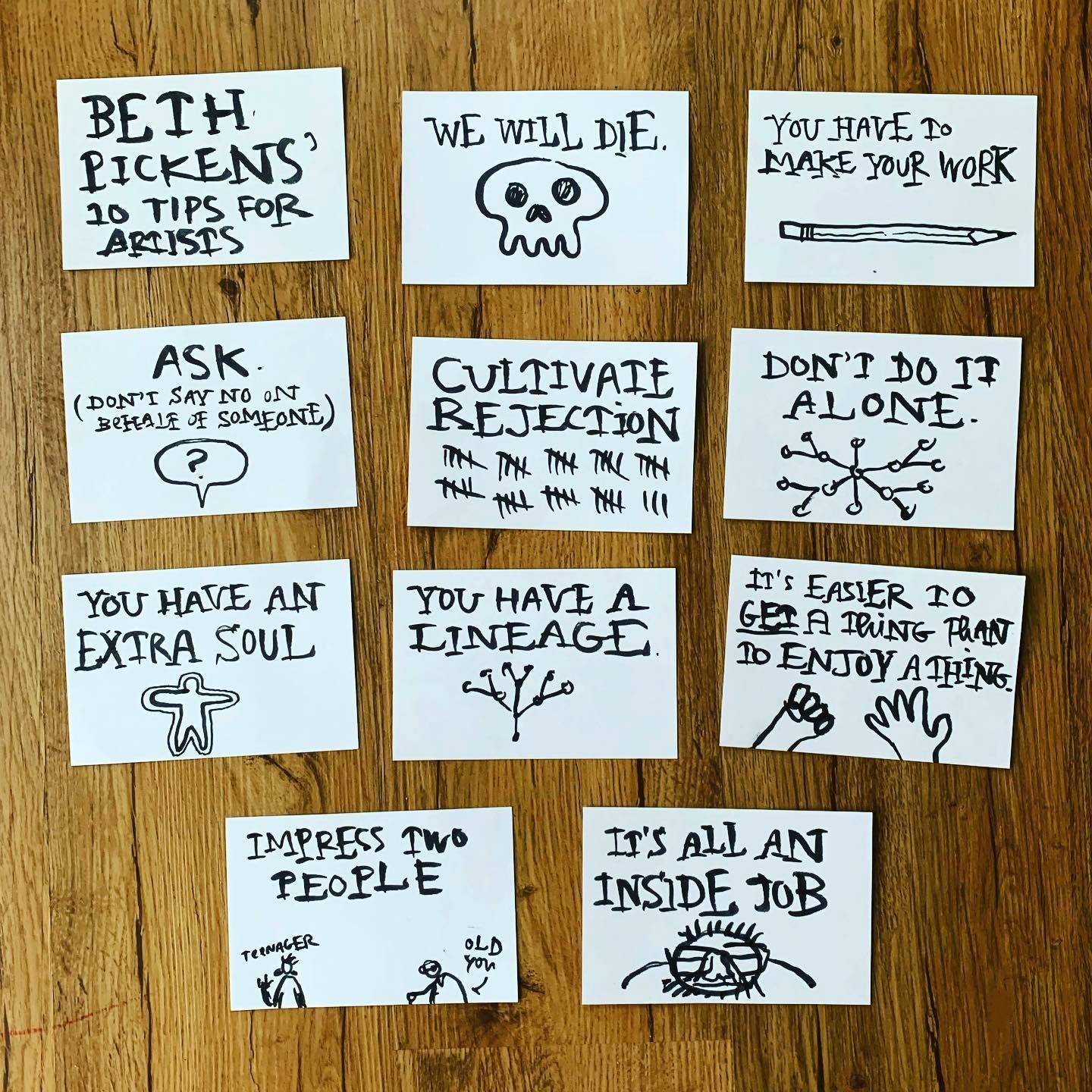

Beth started out with a list of 10 tips for artists based on the things her clients are dealing with right now. I drew them out on index cards:

Beth converted to Judaism by way of feminism (all the feminist writers she liked were Jewish) and I really enjoy hearing about how her religious practice has influenced her work. She hipped me to the importance of taking a day off and Rabbi Heschel’s The Sabbath, which has become one of my favorite books.

Before our conversation, I re-read my notes in her books and wrote them out on index cards as a way to refresh.

Beth believes that the artist needs to do 3 things:

- Consume as much art as they can.

- Join a community of artists and build relationships.

- Make their art no matter what.

In other words: steal, share, and keep going.

My favorite idea of Beth’s is that artists suffer when they don’t make their art.

“Artists are people who are profoundly compelled to make their creative work,” she writes, “and when they are distanced from their practice, their life quality suffers.”

For years, the message I got was: If you can do anything else, you should. *That confused me, because I thought, *Well, sure, I could do anything else. I could be a damned surgeon if I wanted to! *But now I know that if I don’t do creative work… I suffer. I’m not a whole person. If I don’t show up to the studio, it’s harder to show up for the people in my life. (A lesson I learned the hard way as a young dad.) Sure, I *could do something else, but to not have a creative practice would diminish me and make me a not-so-nice person to be around.

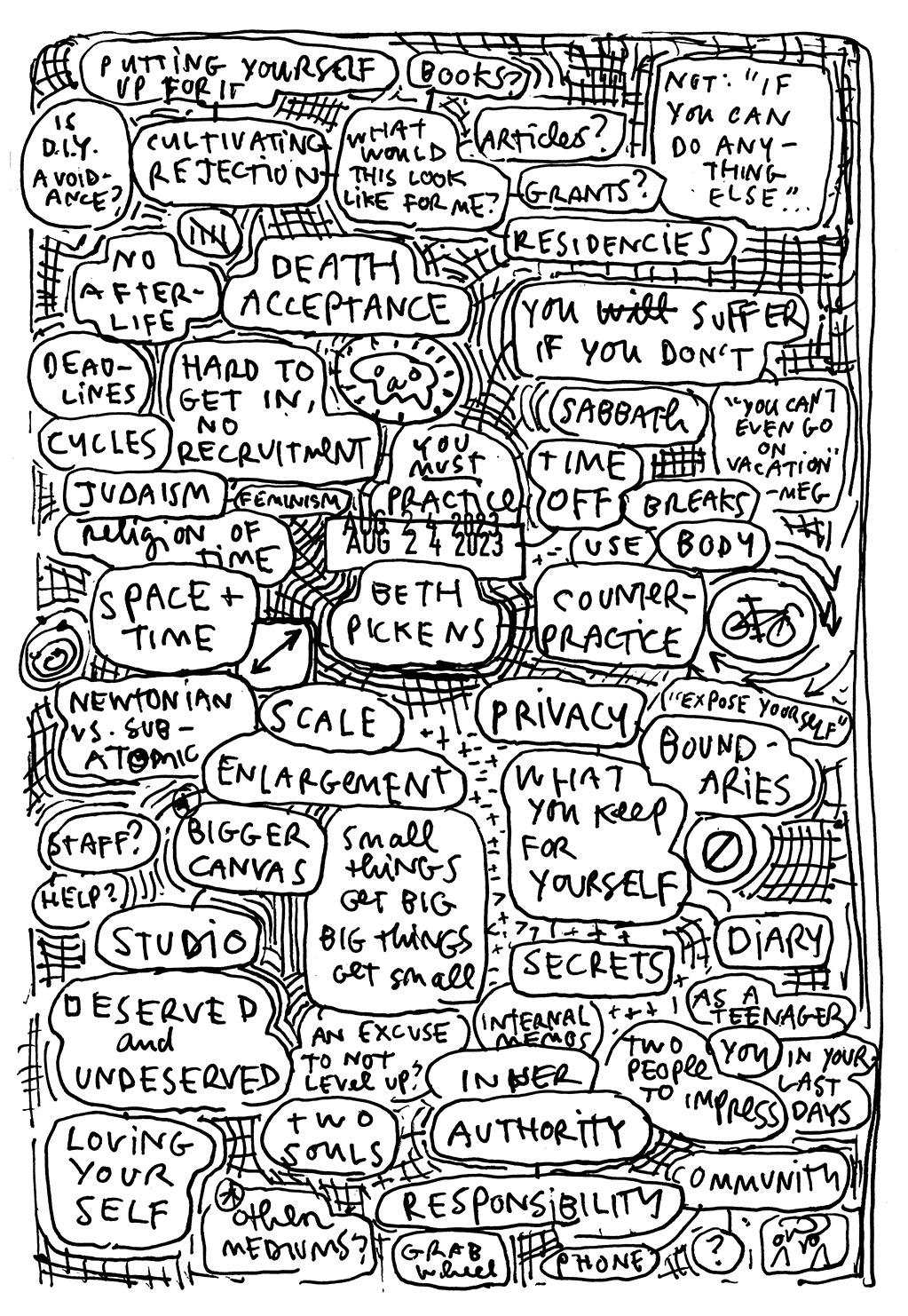

Here are more (personal) notes I doodled from our chat:

As always, I’d love to hear what resonates with y’all and what you’d like to hear more about.

And if you’d like to check out Beth’s Homework Club, she’s offered our gang a discount code with one free month off: MakeYourWork.

xoxo,

Austin

3-2-1: On the shortness of life, what mastery requires, and how to overlap the things you love

3 IDEAS FROM ME

I.

“Move toward the next thing, not away from the last thing.

Same direction. Completely different energy.”

II.

“Guilt lives in the past.

Worry lives in the future.

Peace lives in the present.”

III.

“Mastery requires lots of practice. But the more you practice something, the more boring and routine it becomes.

Thus, an essential component of mastery is the ability to maintain your enthusiasm. The master continues to find the fundamentals interesting.”

2 QUOTES FROM OTHERS

I.

Novelist and poet Robert Louis Stevenson on the shortness of life:

“Old and young, we are all on our last cruise.”

Source: **Crabbed Age and Youth (1877)

II.

Travel writer and essayist Alice Wellington Rollins on the importance of drive:

“The test of a student is not how much he knows, but how much he wants to know.”

Source: **Aphorisms for the Year (1897)

1 QUESTION FOR YOU

How can I overlap the things I enjoy?

For example, maybe you want to exercise and spend time with your spouse. What type of exercise sounds fun to do with your spouse?

Or perhaps you’d like to hang out with friends and build your career. How can you find ways to work with people you like being around?

It doesn’t always work, but there are usually a few areas of life you can overlap in an enjoyable way. Look for the overlap.

Until next week,

James Clear

Atomic Habits**, the #1 best-selling book

*Atoms**, the official Atomic Habits app *

3-2-1 newsletter** with 3 million subscribers

The Enduring Metal Genius of Metallica

The merch preceded them. Forty-eight hours before Metallica performed in Las Vegas, restaurants and bars along the Strip were crammed full of pilgrims dressed in branded gear: T-shirts, jerseys, sweatshirts, sneakers, tank tops, hats, beanies, socks, wristwatches. The most grizzled devotees wore fraying denim vests decorated with several decades’ worth of patches. Metallica’s licensing team estimates that about a hundred and twenty million Metallica T-shirts have been sold since 1995. The motifs are iconic. There’s the one where a hand clutching a dagger emerges from a toilet, alongside the phrase “Metal Up Your Ass.” There’s the one where a skull is wearing scrubs and performing brain surgery with a fork, a knife, and its fangs. There’s the one where the skull has a fistful of stumpy straws and is announcing, “This shortest straw has been pulled for you!” You get the idea.

Metallica is now in its forty-first year. The band was a progenitor, along with Slayer, Anthrax, and Megadeth, of thrash, a subgenre of heavy metal marked by thick, suffocating riffs, played with astonishing speed. Lyrical themes include death, despair, power, grief, and wrath. Though metal is often dismissed as underground music—frantic, savage, niche—Metallica has sold some hundred and twenty-five million records to date, putting the band on par, commercially, with Bruce Springsteen and Jay-Z. It is the only musical group to have performed on all seven continents in a single calendar year. (In 2013, Metallica played a ten-song set in Antarctica for a group of research scientists and contest winners; because of the fragile ice formations, the band’s amplifiers were placed in isolation cabinets, and the concert was broadcast through headphones.) Since 1990, every Metallica album has débuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200.

In 2009, Metallica was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. A speech was given by Flea, the bassist for the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who described the band’s music as “this beautiful, violent thing that was unlike anything I’d ever heard before in my life,” and called its motivation pure. “This is outsider music, and for it to do what it has done is truly mind-blowing,” he said. Metallica is the only metal group to have had its music added to the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress. Kim Kardashian has been photographed in a Metallica shirt on at least two occasions. Beavis sported one for the entire nine-season run of “Beavis and Butt-Head.” Though the band has made adjustments to its sound through the years—some minor, some seismic, all irritating to certain subsets of its fan base—it’s hard to think of another act that has outlasted the whims of the culture with such vigor. The band recently finished writing and recording its eleventh record, which will be released next year. “Metallica are the Marines of metal,” Scott Ian, a founder of Anthrax, told me recently. “First one in, last one out.”

Metallica’s current lineup includes the singer and rhythm guitarist James Hetfield and the drummer Lars Ulrich, both of whom co-founded the band; the lead guitarist Kirk Hammett, who joined in 1983; and the bassist Robert Trujillo, a member since 2003. Hetfield—fifty-nine, tall, graying at the temples—moves with the confident saunter of a well-armed cowboy. Ulrich, fifty-eight, radiates so much kinetic energy that it’s hard to imagine him yawning. Hammett, fifty-nine, and Trujillo, fifty-eight, are the band’s gentle, long-haired surfers, jazz enthusiasts disinclined to dramatics. If Hetfield is Metallica’s heart—its musical center and primary lyricist—Ulrich is its brain, a visionary who instinctively understands cultural terrain.

The night before the Vegas show, the band gathered at Allegiant Stadium for sound check. A scrum of about a dozen people, mostly from Metallica’s touring crew, stood on the floor to watch. (The band’s full road team has at least a hundred members.) Derek Carr, the quarterback for the Las Vegas Raiders, appeared, looking as though he were resisting an intense urge to play air guitar. Some clients of the private-plane company NetJets sat in the stands, enjoying specialty cocktails and cheering. The band periodically gathered around Ulrich’s drum kit. “Is there anything anyone wants to run?” Ulrich asked. But everyone knew what to do. At one point, Trujillo glanced out at the vacant seats and dad-joked, “I thought we were playing a sold-out show.” Even in a mostly empty stadium, the band sounded powerful, lucid, heavy.

The next afternoon, a pre-show event was scheduled for the House of Blues, somewhere in the belly of the Mandalay Bay casino. I sent a series of increasingly disoriented texts to a friend—“I’m in the casino, where are you?” “I’m in the casino?”—before we found each other. We were both wearing vintage T-shirts featuring the cemetery-themed art from “Master of Puppets,” the band’s third album.

At the bar, we lined up for plastic cups of the band’s own Blackened whiskey, a bourbon-rye blend that’s finished in brandy casks while Metallica songs blare from large speakers. A product description credits the music with enhancing the spirit’s flavor: “The whiskey is pummeled by low-hertz soundwaves which force the whiskey deeper into the wood of the barrel, where it picks up additional wood flavor characteristics.” It tasted nice. You could feel an anticipatory flutter in the air. COVID-19 had grounded Metallica for long stretches of 2020 and 2021. (My backstage pass featured a skull with a wispy Mohawk self-administering a COVID test—the results, of course, were positive.) Fans were slapping one another on the back, hooting about how much they had missed this. The feeling was: Let’s pop off. People were ready to have a good-ass time—to drink too many beers, to forget their earplugs, to buy a new Metallica T-shirt with demons on it and wiggle it on over an old Metallica T-shirt with demons on it, to headbang, to contort their fingers into devil’s horns and thrust them upward, to go “Ahhh!” when the pyro shot off, to shriek “Searching . . . seek and destroy!” along with fifty thousand other wild-eyed people, to turn to a friend and mouth “Yo!” when someone was soloing. Greta Van Fleet, a young rock band from Michigan, was opening for Metallica throughout the year. “Metallica has curated their own culture, and you can see the impact that’s had when you look out into the audience,” Greta Van Fleet’s singer, Josh Kiszka, told me. “Driving to the venue, it’s Metallica everywhere. That’s part of how the band has changed the world a little bit.”

From afar, it is easy to see Metallica as an instigating force—an accelerant, turning unruly hooligans more unruly. But that idea alone can’t sustain a devoted following for decades. As we sipped our whiskey, my companion, August Thompson, a Metallica fan since his boyhood in rural New Hampshire, told me his favorite lyric, from “Escape,” a thick and charging song from “Ride the Lightning” (1984): “Life’s for my own, to live my own way.” Hetfield repeats the sentiment, with slightly different phrasing, on “Nothing Else Matters,” a song from “Metallica” (1991): “Life is ours, we live it our way.” “For people like me, who always felt out of place in a hyper-violent world, and the hyper-violence that is masculinity, there’s a lot of solace in that,” Thompson said. Metallica’s music is rooted in feelings of marginalization, and the band, despite its achievements, has found a way to maintain that point of view for more than forty years. It makes sense that people are drawn to Metallica’s music, because they’re ill at ease in a culture that relentlessly valorizes things (money, love, straight teeth) that are very easy to be born without.

That night, Metallica opened its set with “Whiplash,” from “Kill ’Em All,” its début album. On the floor, mosh pits formed; from the stands, they resembled tiny riptides, bodies circling one another, sometimes submitting to a menacing current but mostly just orbiting. If you squinted, it almost looked like an ancient folk dance—something that might happen at a Greek wedding, late, after people had been drinking. “I think the best seat in the arena is the second tier up, where you get to see the band but you also get to see all the fans,” Hetfield told me later. “Forget the band—look at the audience.”

These days, the set list is mostly old songs, and the vibe is largely benevolent. Hetfield’s voice is low and scratchy, and can shift from contemplative to feral in a single note. He is prone to ending his phrases with a tight, curled snarl. He can still transform a “Yeah!” into a vast and terrifying invocation. He can also be tender and earnest, which has recently led fans to call him Papa Het. “This song goes out to all who struggle,” Hetfield said before “Fade to Black,” a ballad about suicide. “If you think you’re the only one, it’s a lie. You can talk to your friends, talk to somebody, because you are not alone.”

The band closed its encore with “Enter Sandman,” another single from “Metallica.” Even if metal is not your bag, it’s hard to deny the menacing perfection of the song’s opening riff: an E-minor chord, a wah-wah pedal, a sense that something dark and creepy is about to happen. During the chorus, I looked over at Thompson, who had the dazed and exuberant look of someone who had been cured of a disease by an itinerant preacher. All around us, people were rapt, ecstatic, and free. “I get up there and sing, and I watch people change,” Hetfield told me.

Hetfield was born in Downey, California, in 1963. His mother, Cynthia, had two sons from a previous marriage. His father, Virgil, had fought in the Second World War and started a trucking company when he returned to California. “He did not have a great childhood,” Hetfield said of his father. “My grandfather was some crazy musician who came through town, and then off he went—imagine that,” he added, laughing. His parents were devout Christian Scientists, and had met in church, where Virgil helped lead a weekly service. But Hetfield never connected with the religion. “It felt lonely,” he said. “When my dad was up there reading from the Scriptures, he was getting tears in his eyes. It moved him. I didn’t get it. I thought something was wrong with me.” Hetfield recalled being embarrassed when he wasn’t allowed to attend health class, or receive a physical to play football. “I still carry shame about that,” he said. “How different we were to people.”

When Hetfield was thirteen, his father left. “I went off to church camp, and I came back and he was gone,” he recalled. Two years later, his mother developed cancer, but refused medical treatment on religious grounds. “We watched her wither to nothing,” he said. “She had religion around her, inside her. She had practitioners coming over. But the cancer was stronger.” Hetfield is still not entirely sure what type of cancer she had. “Probably something really curable,” he said. For a long time, Hetfield was angry that his mother had rebuffed doctors. “I thought she cared more about religion than she did her kids,” he said. “It wasn’t talked about, either—if you’re talking about it, you’re giving it power, and you want to take power away from it. So admitting that you’re sick, that’s a no-no. We just saw it happening.” Cynthia died when Hetfield was sixteen. “There was nothing solid to stand on,” he said. “I felt extremely lost.” On “The God That Failed,” an angry, punishing cut from “Metallica,” Hetfield sings about the experience: “Broken is the promise, betrayal / The healing hand held back by the deepened nail.”

Ulrich had a very different sort of childhood. He was born in Gentofte, Denmark, in 1963. His father, Torben, was both a professional tennis player and a jazz critic (the saxophonist Dexter Gordon was Ulrich’s godfather), and his family was worldly and cultured. (“We ate McDonald’s, he ate herring,” Hetfield once said of the cultural divide.) Ulrich came to the U.S. in 1979, when he was fifteen, to attend tennis camp. He ended up at the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy, in Bradenton, Florida. He had been a promising youth player in Denmark, but he found the strictures of American athletic training stifling. “Curfew at 9 P.M., ten o’clock lights out, four to a bunk room, and then wake up and eat cornflakes and start hitting forehands down the line for four hours, and then backhands crosscourt for the next four hours,” he said. “That was just too stringent and disciplined for me.” When Ulrich was sixteen, his family relocated to Newport Beach, California. “In Denmark, I was at the very top end of my age group in the whole country,” he said. “When I went to qualify for the tennis team at Corona del Mar High School, I wasn’t one of the seven best tennis players at Corona del Mar High School. I don’t think I was one of the seven best tennis players on the street that I lived on.” Ulrich switched his focus to music. He was captivated by what was then called the New Wave of British Heavy Metal—bands that mixed the fury and speed of punk rock with the density and danger of metal. “When people would go, ‘Heavy metal? You mean like Kansas and Van Halen and Styx and Journey?,’ I’d go, ‘No, like Angel Witch or Saxon or Diamond Head or the Tygers of Pan Tang,’ ” he said.

“He’s guarding against plaque.”Cartoon by Michael Maslin

Link copied

In 1981, Ulrich, seeking musicians interested in starting a band, placed a classified ad in the back of The Recycler, a free periodical that was originally known as E-Z Buy E-Z Sell. A friend of Hetfield’s answered the ad, and Hetfield tagged along. “He was painfully shy,” Ulrich said. “We instantly bonded over the fact that we were loners and outsiders, and open to a best-friend relationship. Neither of us had really found who we were yet.” Though their approaches to songwriting were different—“He looks at music as a math equation, I look at it as a flowing river,” Hetfield said—they complemented each other. “Both of us were dreamers. At our best, our relationship was completely free of competitive energy or one-up-ness,” Ulrich said. “But then when there were other people in the room it became ‘Who is leading?’ ”

Hetfield and Ulrich recruited a second guitarist, Dave Mustaine, by placing another ad in The Recycler. In 1982, Hetfield and Ulrich saw a group called Trauma perform at the Whisky a Go Go, a club on the Sunset Strip. They were awed by Cliff Burton, Trauma’s twenty-year-old bass player, and began trying to persuade him to join Metallica. Scott Ian, of Anthrax, said, “There was Cliff in his flares and his Lynyrd Skynyrd pin”—an affront to the punk-indebted aesthetics of the thrash scene, which included leather jackets, hefty boots, and studded belts. Unlike the members of Metallica, Burton had some musical training. He played fingerpicked bass with the boldness and harmonic sophistication of a guitarist. “He was always doing tricky stuff that would make me think, Fuck, man, where is this guy getting this from?” Kirk Hammett said. “He was just so . . . musical.”

In order to get Burton, who was based in El Cerrito, a small city across the bay from San Francisco, Hetfield and Ulrich agreed to move there, renting an unassuming house on Carlson Boulevard and rehearsing in the garage. Mustaine moved into a unit on Burton’s grandmother’s property. Times were lean. “We’d find a tomato and some mayonnaise and make tomato sandwiches and think we were highbrow metalheads,” Mustaine recalled. Ulrich described the band’s early days as feeling immediate, uncomplicated: “There was only that moment, and ‘Where’s the beer?’ ”

In early 1983, Metallica was signed by Jonny Zazula—better known as Jonny Z.—a part-time concert promoter who sold heavy-metal records at an indoor flea market on Route 18 in East Brunswick, New Jersey. It was still difficult to buy imported metal albums at mainstream record shops, and a scene of sorts had sprung up around Zazula’s booth. One weekend, Zazula asked Scott Ian if he wanted to hear “No Life ’Til Leather,” a seven-song demo that Metallica recorded before Burton joined. The songs were raw and deranged, distinguished by the band’s adolescent mania and Hetfield’s tendency to down-pick, which resulted in a thicker, heavier feel. “Holy fuck,” Ian said. “Nothing sounded like that before Metallica. Straight up. It was like electricity was coming out of the tape player. Jonny Z. said, ‘I’m bringing them to New York. We’re gonna make an album.’ I’m, like, ‘You know how to do that?’ And he goes, ‘No!’ ”

Zazula and his wife, Marsha, founded Megaforce Records after shopping the Metallica demo around and failing to get an offer. When the Zazulas started Megaforce, Jonny Z. was serving a six-month sentence in a halfway house, for conspiracy to commit wire fraud. (He’d been employed by a company that passed off scrap metal as tantalum, a rare element used in the manufacture of capacitors.) He spent his weekdays feeding quarters into a pay phone, attempting to book shows. “I just got caught in this passion, like there’s this little Led Zeppelin hanging out in El Cerrito, you know?” Zazula, who died earlier this year, told Mick Wall, the author of “Enter Night: A Biography of Metallica.” Zazula sent the band members fifteen hundred dollars so they could drive east in a U-Haul with their gear. In “Mustaine,” a 2010 autobiography, Mustaine remembers rolling out of bed, “bleary eyed, hungover, and smelling like bad cottage cheese,” and noticing the truck parked out front. “We stopped for beer less than a mile after pulling out of the driveway and remained in a drunken stupor for most of the trip,” he wrote.