Engineering for Slow Internet

![]()

Hello everyone! I got partway through writing this post while I was still in Antarctica, but I departed before finishing it.

I’m going through my old draft posts, and I found that this one was nearly complete.

It’s a bit of a departure from the normal content you’d find on brr.fyi, but it reflects my software / IT engineering background.

I hope folks find this to be an interesting glimpse into the on-the-ground reality of using the Internet in bandwidth-constrained environments.

Please keep in mind that I wrote the majority of this post ~7 months ago, so it’s likely that the IT landscape has shifted since then.

Welcome back for a bonus post about Engineering for Slow Internet!

For a 14-month period, while working in Antarctica, I had access to the Internet only through an extremely limited series of satellite links provided by the United States Antarctic Program.

Before I go further, this post requires a special caveat, above and beyond my standard disclaimer:

Even though I was an IT worker within the United States Antarctic Program, everything I am going to discuss in this post is based on either publicly-available information, or based on my own observations as a regular participant living on ice.

I have not used any internal access or non-public information in writing this post.

As a condition of my employment, I agreed to a set of restrictions regarding public disclosure of non-public Information Technology material. I fully intend to honor these restrictions. These restrictions are ordinary and typical of US government contract work.

It is unlikely that I will be able to answer additional questions about matters I discuss in this post. I’ve taken great care to write as much as I am able to, without disclosing non-public information regarding government IT systems.

Good? Ok, here we go.

… actually wait, sorry, one more disclaimer.

This information reflects my own personal experience in Antarctica, from August 2022 through December 2022 at McMurdo, and then from December 2022 through November 2023 at the South Pole.

Technology moves quickly, and I make no claims that the circumstances of my own specific experience will hold up over time. In future years, once I’ve long-since forgotten about this post, please do not get mad at me when the on-the-ground IT experience in Antarctica evolves away from the snapshot presented here.

Ok, phew. Here we go for real.

It’s a non-trivial feat of engineering to get any Internet at the South Pole! If you’re bored, check out the South Pole Satellite Communications page on the public USAP.gov website, for an overview of the limited selection of satellites available for Polar use.

If you’re interested, perhaps also look into the 2021 Antarctic Subsea Cable Workshop for an overview of some hurdles associated with running traditional fiber to the continent.

I am absolutely not in a position of authority to speculate on the future of Antarctic connectivity! Seriously. I was a low-level, seasonal IT worker in a large, complex organization. Do not email me your ideas for improving Internet access in Antarctica – I am not in a position to do anything with them.

I do agree with the widespread consensus on the matter: There is tremendous interest in improving connectivity to US research stations in Antarctica. I would timidly conjecture that, at some point, there will be engineering solutions to these problems. Improved connectivity will eventually arrive in Antarctica, either through enhanced satellite technologies or through the arrival of fiber to the continent.

But – that world will only exist at some point in the future. Currently, Antarctic connectivity is extremely limited. What do I mean by that?

Until very recently, at McMurdo, nearly a thousand people, plus numerous scientific projects and operational workloads, all relied on a series of links that provided max, aggregate speeds of a few dozen megabits per second to the entire station. For comparison, that’s less bandwidth shared by everyone combined than what everyone individually can get on a typical 4g cellular network in an American suburb.

Things are looking up! The NSF recently announced some important developments regarding Starlink at McMurdo and Palmer.

I’m aware that the on-the-ground experience in McMurdo and Palmer is better now than it was even just a year ago.

But – as of October 2023, the situation was still pretty dire at the South Pole. As far as I’m aware, similar developments regarding Starlink have not yet been announced for South Pole Station.

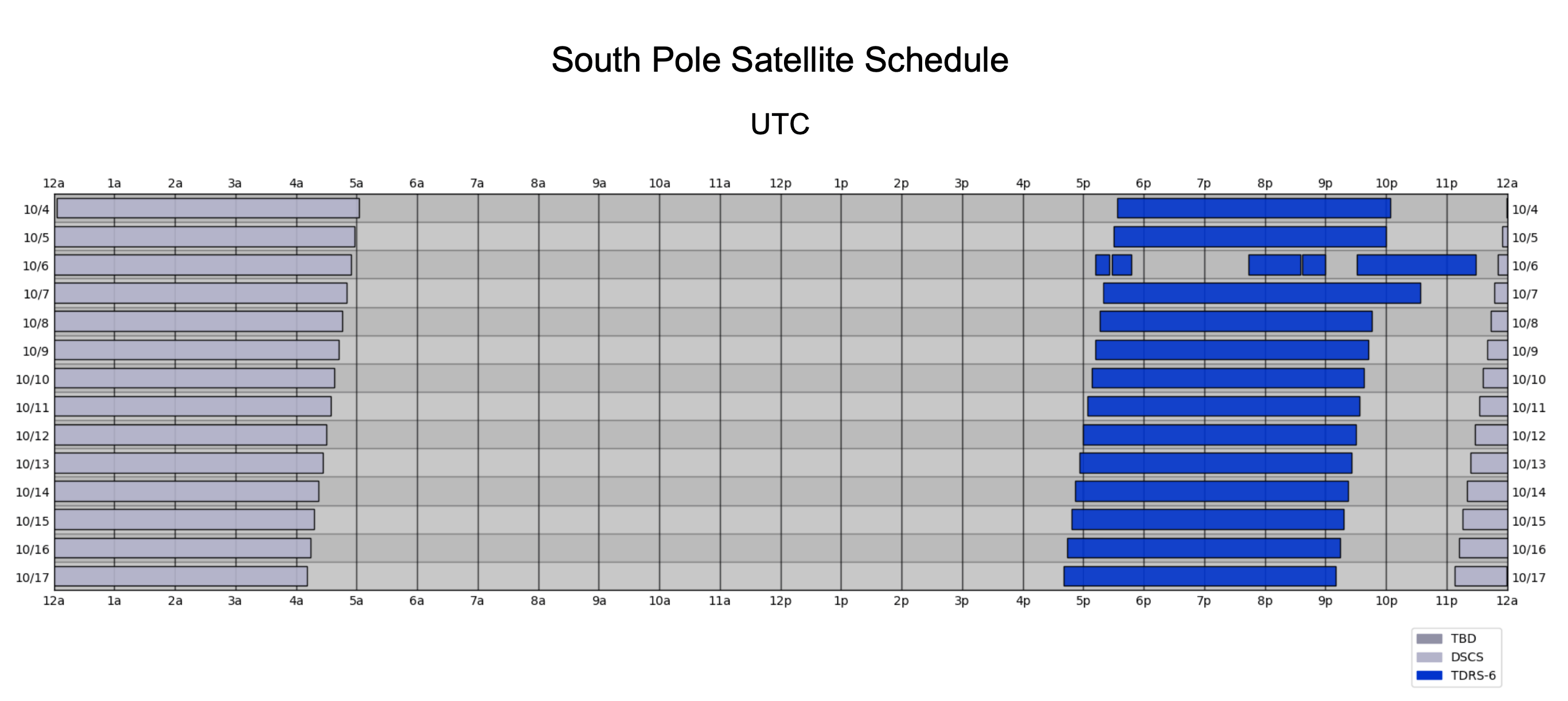

As of October 2023, South Pole had the limitations described above, plus there was only connectivity for a few hours a day, when the satellites rose above the horizon and the station was authorized to use them. The satellite schedule generally shifts forward (earlier) by about 4 minutes per day, due to the difference between Sidereal time and Solar (Civil) time.

The current satellite schedule can be found online, on the South Pole Satellite Communications page of the public USAP.gov website. Here’s an example of the schedule from October 2023:

South Pole satellite schedule, for two weeks in October 2023.

These small intermittent links to the outside world are shared by everyone at Pole, for operational, science, and community / morale usage.

Complicating matters further is the unavoidable physics of this connectivity. These satellites are in a high orbit, thousands of miles up. This means high latency. If you’ve used a consumer satellite product such as HughesNet or ViaSat, you’ll understand.

From my berthing room at the South Pole, it was about 750 milliseconds, round trip, for a packet to get to and from a terrestrial US destination. This is about ten times the latency of a round trip between the US East and West coasts (up to 75 ms). And it’s about thirty times the expected latency of a healthy connection from your home, on a terrestrial cable or fiber connection, to most major content delivery networks (up to 25 ms).

Seriously, I can’t emphasize how jarring this is. At my apartment back home, on GPON fiber, it’s about 3 ms roundtrip to Fastly, Cloudflare, CloudFront, Akamai, and Google. At the South Pole, the latency was over two hundred and fifty times greater.

I can’t go into more depth about how USAP does prioritization, shaping, etc, because I’m not authorized to share these details. Suffice to say, if you’re an enterprise network engineer used to working in a bandwidth-constrained environment, you’ll feel right at home with the equipment, tools, and techniques used to manage Antarctic connectivity.

Any individual trying to use the Internet for community use at the South Pole, as of October 2023, likely faced:

- Round-trip latency averaging around 750 milliseconds, with jitter between packets sometimes exceeding several seconds.

- Available speeds, to the end-user device, that range from a couple kbps (yes, you read that right), up to 2 mbps on a really good day.

- Extreme congestion, queueing, and dropped packets, far in excess of even the worst oversaturated ISP links or bufferbloat-infested routers back home.

- Limited availability, frequent dropouts, and occasional service preemptions.

These constraints drastically impact the modern web experience! Some of it is unavoidable. The link characteristics described above are truly bleak. But – a lot of the end-user impact is caused by web and app engineering which fails to take slow/intermittent links into consideration.

If you’re an app developer reading this, can you tell me, off the top of your head, how your app behaves on a link with 40 kbps available bandwidth, 1,000 ms latency, occasional jitter of up to 2,000 ms, packet loss of 10%, and a complete 15-second connectivity dropout every few minutes?

It’s probably not great! And yet – these are real-world performance parameters that I encountered, under certain conditions, at the South Pole. It’s normally better than this, but this does occur, and it occurs often enough that it’s worth taking seriously.

This is what happens when you have a tiny pipe to share among high-priority operational needs, plus dozens of community users. Operational needs are aggressively prioritized, and the community soaks up whatever is left.

I’m not expecting miracles here! Obviously no amount of client engineering can make, say, real-time video conferencing work under these conditions. But – getting a few bytes of text in and out should still be possible! I know it is possible, because some apps are still able to do it. Others are not.

Detailed, Real-world Example

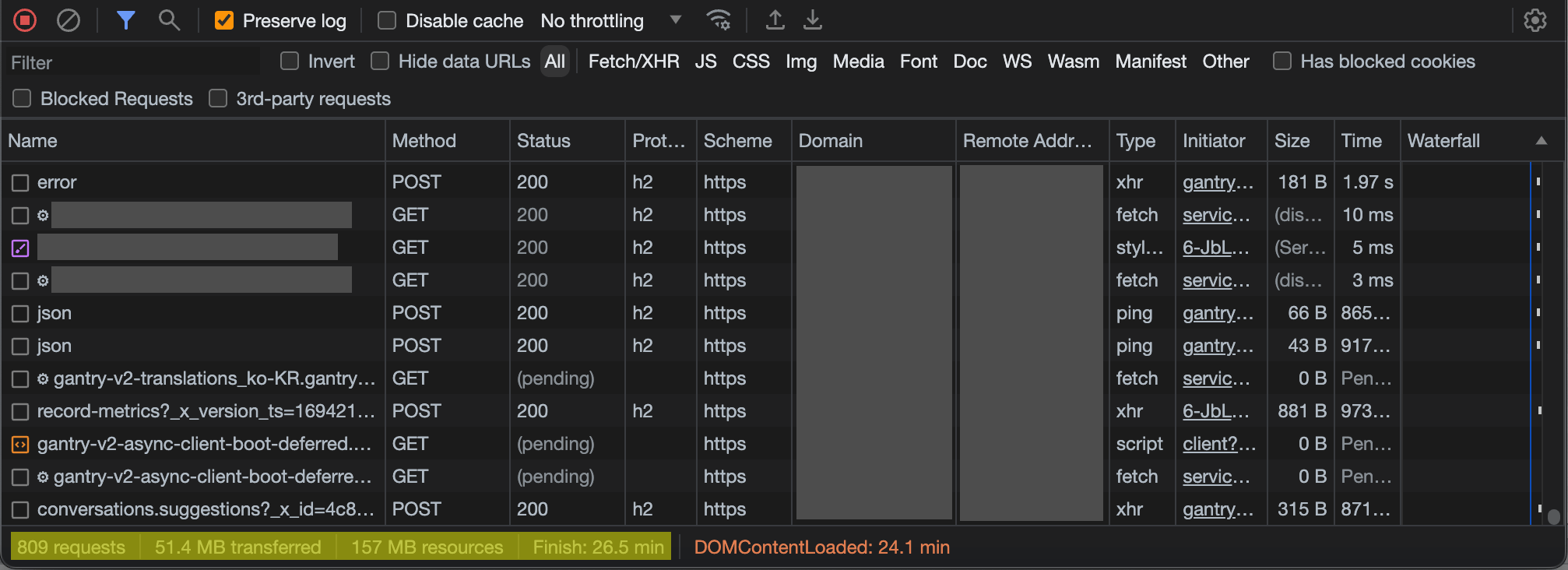

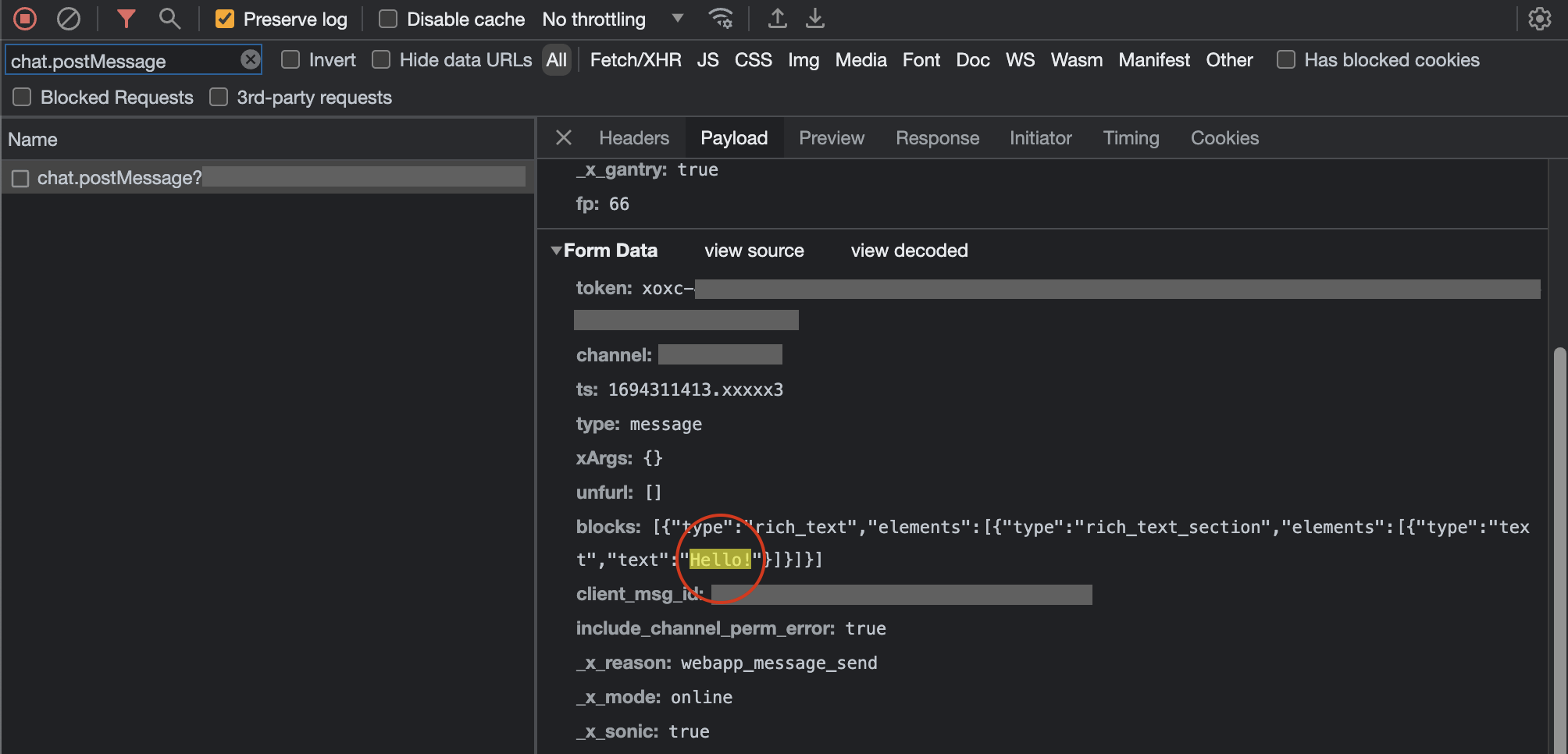

One day at the South Pole, I was trying to load the website of <$enterprise_collaboration_platform> in my browser. It’s huge! It needed to load nearly 20 MB of Javascript, just to render the main screen! And of course, the app had been updated since last time I loaded it, so all of my browser’s cached assets were stale and had to be re-downloaded.

Fine! It’s slow, but at least it will work… eventually, right? Browsers do a decent job of handling slow Internet. Under the hood, the underlying protocols do a decent job at congestion control. I should get a steady trickle of data. This will be subject to the negotiated send and receive windows between client and server, which are based on the current level of congestion on the link, and which are further influenced by any shaping done by middleware along the way.

It’s a complex webapp, so the app developer would also need to implement some of their own retry logic. This allows for recovery in the event that individual assets fail, especially for those long, multi-second total connectivity dropouts. But eventually, given enough time, the transfers should complete.

Unfortunately, this is where things broke down and got really annoying. The developers implemented a global failure trigger somewhere in the app. If the app didn’t fully load within the parameters specified by the developer (time? number of retries? I’m not sure.), then the app stopped, gave up, redirected you to an error page, dropped all the loading progress you’d made, and implemented aggressive cache-busting countermeasures for next time you retried.

I cannot tell you how frustrating this was! Connectivity at the South Pole was never going to meet the performance expectations set by engineers using a robust terrestrial Internet connection. It’s not a good idea to hardcode a single, static, global expectation for how long 20 MB of Javascript should take to download. Why not let me load it at my own pace? I’ll get there when I get there. As long as data is still moving, however slow, just let it run.

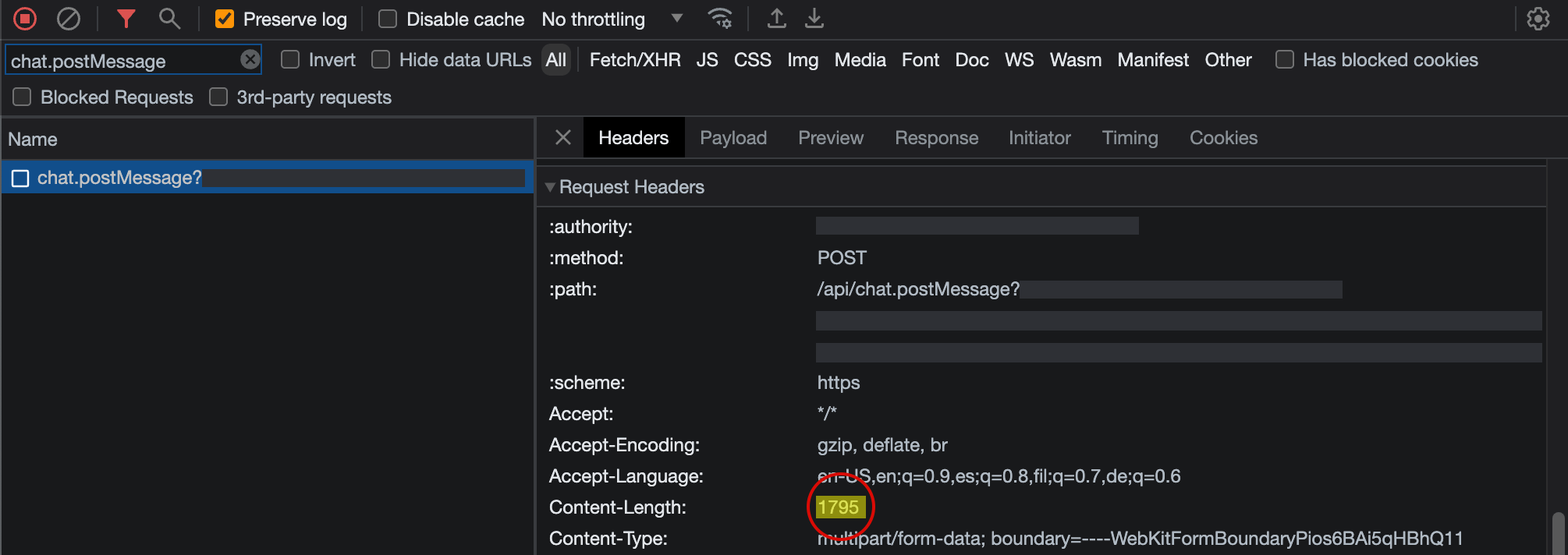

But – the developers decided that if the app didn’t load within the parameters they set, I couldn’t use it at all. And to be clear – this was primarily a messaging app. The actual content payload here, when the app is running and I’m chatting with my friends, is measured in bytes.

As it turns out, our Internet performance at the South Pole was right on the edge of what the app developers considered “acceptable”. So, if I kept reloading the page, and if I kept letting it re-download the same 20 MB of Javascript, and if I kept putting up with the developer’s cache-busting shenanigans, eventually it finished before the artificial failure criteria.

What this means is that I wasted extra bandwidth doing all these useless reloads, and it took sometimes hours before I was able to use the app. All of this hassle, even though, if left alone, I could complete the necessary data transfer in 15 minutes. Several hours (and a shameful amount of retried Javascript) later, I was finally able to send a short, text-based message to my friends.

…all so that I could send a 1.8 KB HTTPS POST…

Does this webapp really need to be 20 MB? What all is being loaded that could be deferred until it is needed, or included in an “optional” add-on bundle? Is there a possibility of a “lite” version, for bandwidth-constrained users?

In my 14 months in Antarctica, I collected dozens of examples of apps like this, with artificial constraints built in that rendered them unusable or borderline-unusable.

For the rest of this post, I’ll outline some of my major frustrations, and what I would have liked to see instead that would mitigate the issues.

I understand that not every app is in a position to implement all of these! If you’re a tiny app, just getting off the ground, I don’t expect you to spend all of your development time optimizing for weirdos in Antarctica.

Yes, Antarctica is an edge case! Yes, 750 ms / 10% packet loss / 40 kbps is rather extreme. But the South Pole was not uniquely bad. There are entire commercial marine vessels that rely on older Inmarsat solutions for a few hundred precious kbps of data while at sea. There’s someone at a remote research site deep in the mountains right now, trying to load your app on a Thales MissionLink using the Iridium Certus network at a few dozen kbps. There are folks behind misconfigured routers, folks with flaky wifi, folks stuck with fly-by-night WISPs delivering sub-par service. Folks who still use dial-up Internet connections over degraded copper phone lines.

These folks are worthy of your consideration. At the very least, you should make an effort to avoid actively interfering with their ability to use your products.

So, without further ado, here are some examples of development patterns that routinely caused me grief at the South Pole.

Hardcoded Timeouts, Hardcoded Chunk Size

As per the above example, do not hardcode your assumptions about how long a given payload will take to transfer, or how much you can transfer in a single request.

- If you have the ability to measure whether bytes are flowing, and they are, leave them alone, no matter how slow. Perhaps show some UI indicating what is happening.

- If you are doing an HTTPS call, fall back to a longer timeout if the call fails. Maybe it just needs more time under current network conditions.

- If you’re having trouble moving large amounts of data in a single HTTPS call, break it up. Divide the content into chunks, transfer small chunks at a time, and diligently keep track of the progress, to allow resuming and retrying small bits without losing all progress so far. Slow, steady, incremental progress is better than a one-shot attempt to transfer a huge amount of data.

- If you can’t get an HTTPS call done successfully, do some troubleshooting. Try DNS, ICMP, HTTP (without TLS), HTTPS to a known good status endpoint, etc. This information might be helpful for troubleshooting, and it’s better than blindly retrying the same end-to-end HTTPS call. This HTTPS call requires a bunch of under-the-hood stuff to be working properly. Clearly it’s not, so you should make an effort to figure out why and let your user know.

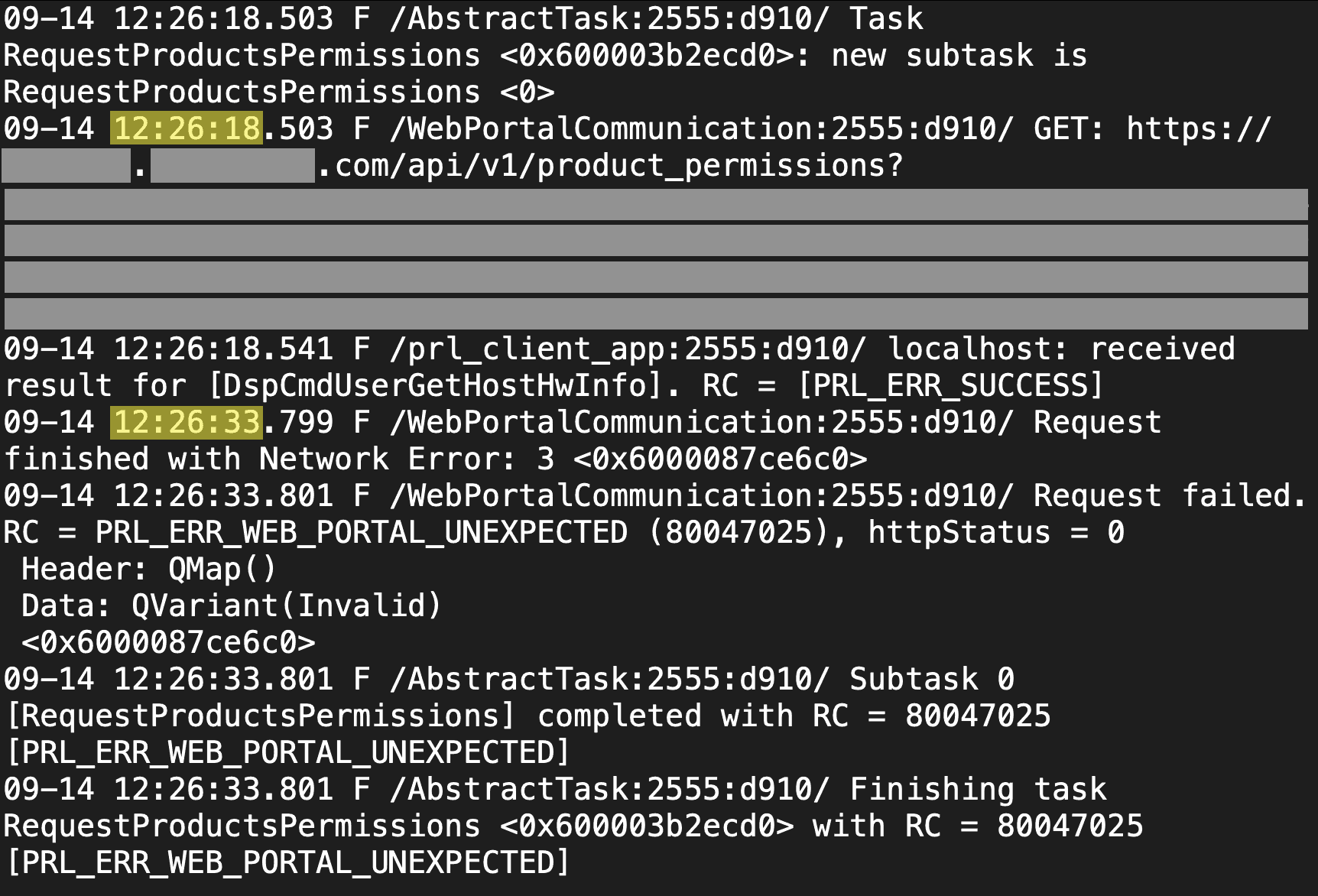

Example 1 - In-App Metadata Download

A popular desktop application tries to download some configuration information from the vendor’s website at startup. There is a hardcoded timeout for the HTTPS call. If it fails, the app will not load. It’ll just keep retrying the same call, with the same parameters, forever. It’ll sit on the loading page, without telling you what’s wrong. I’ve confirmed this is what’s happening by reading the logs.

Luckily, if you kept trying, the call would eventually make it through under network conditions I experienced at the South Pole.

It’s frustrating that just a single hardcoded timeout value, in an otherwise perfectly-functional and enterprise-grade application, can render it almost unusable. The developers could have:

- Fallen back to increasingly-long timeouts to try and get a successful result.

- Done some connection troubleshooting to infer more about the current network environment, and responded accordingly.

- Shown UX explaining what was going on.

- Used a cached or default-value configuration, if it couldn’t get the live one, instead of simply refusing to load.

- Provided a mechanism for the user to manually download and install the required data, bypassing the app’s built-in (and naive) download logic.

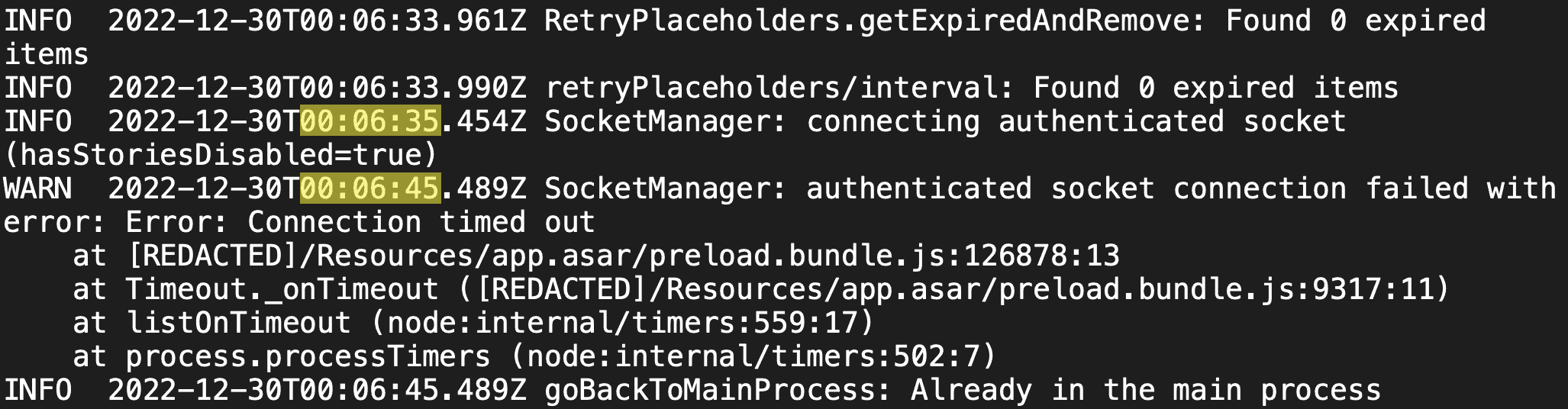

Example 2 - Chat Apps

A popular chat app (“app #1”) maintains a websocket for sending and receiving data. The initialization process for that websocket uses a hardcoded 10-second timeout. Upon cold boot, when network conditions are especially congested, that websocket setup can sometimes take more than 10 seconds! We have to do a full TCP handshake, then set up a TLS session, then set up the websocket, then do initial signaling over the websocket. Remember – under some conditions, each individual roundtrip at the South Pole took multiple seconds!

If the 10-second timeout elapses, the app simply does not work. It enters a very long backoff state before retrying. The UX does not clearly show what is happening.

On the other hand, a competitor’s chat app (“app #2”) does very well in extremely degraded network conditions! It has multiple strategies for sending network requests, for resilience against certain types of degradation. It aggressively re-uses open connections. It dynamically adjusts timeouts. In the event of a failure, it intelligently chooses a retry cadence. And, throughout all of this, it has clear UX explaining current network state.

The end result is that I could often use app #2 in network conditions when I could not use app #1. Both of them were just transmitting plain text! Just a few actual bytes of content! And even when I could not use app #2, it was at least telling me what it was trying to do. App #1 is written naively, with baked-in assumptions about connectivity that simply did not hold true at the South Pole. App #2 is written well, and it responds gracefully to the conditions it encounters in the wild.

Example 3 - Incremental Transfer

A chance to talk about my own blog publishing toolchain!

The site you’re reading right now is a static Jekyll blog. Assets are stored on S3 and served through CloudFront. I build the static files locally here on my laptop, and I upload them directly to S3. Nothing fancy. No servers, no QA environment, no build system, no automated hooks, nothing dynamic.

Given the extreme connectivity constraints at the South Pole, I wrote a Python script for publishing to S3 that worked well in the challenging environment. It uses the S3 API to upload assets in small chunks. It detects and resumes failed uploads without losing progress. It waits until everything is safely uploaded before publishing the new version.

If I can do it, unpaid, working alone, for my silly little hobby blog, in 200 lines of Python… surely your team of engineers can do so for your flagship webapp.